|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Charlotte Rampling Films

- Comedy

- Jessica Harper Films

- Mid-Life Crisis

- Movie Directors

- Woody Allen Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

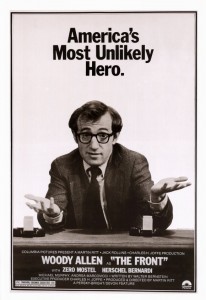

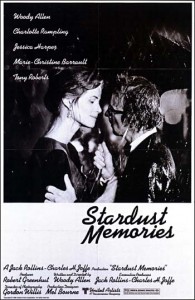

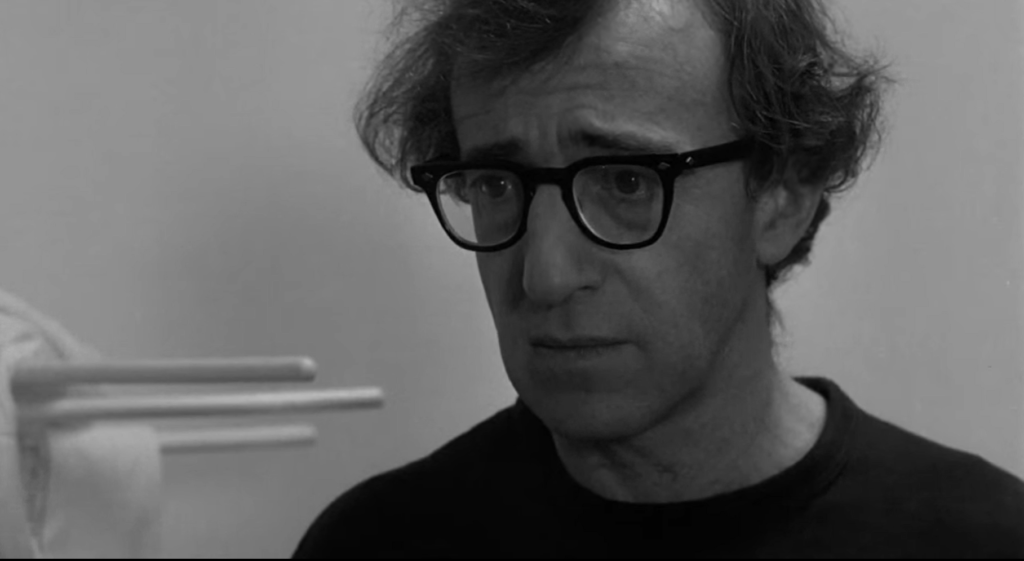

Peary writes that in making Stardust Memories, “Woody Allen takes Fellini’s autobiographical 8 1/2 and applies it, one assumes, to his own life”. He notes that the “picture is [a] daring change of pace for Allen and contains wit and insight into [the] life and thoughts of an Allen-like filmmaker”:

… but argues (somewhat cryptically) that it’s “not a success”, in part because “we don’t really like” Allen’s character, someone “whom we can believe is much like the real Allen”. He concludes his review by asserting that the film “should certainly be funnier”, and notes that “many” (including Peary himself??) “resent the way ‘Allen’s’ fans are depicted.” Indeed, Stardust Memories is a notoriously contentious film in Allen’s oeuvre, though I’ll admit I remain puzzled by this designation. It’s easier to understand critics’ (and audiences’) “resentment” over Allen’s drastic shift away from comedy with Interiors (1978) — but Stardust Memories is drolly amusing enough to classify as a darkly humorous comedy-of-life, even if it’s not as overtly designed for laughs as his “early, funny” pictures (to quote a character in the film itself).

After writing and helming 8-9 full-length films — including such certified classics as Annie Hall (1977) and Manhattan (1979) — and thus revealing himself to be a cinematic auteur of the highest stature, Allen fully “deserved” to make a movie like this, one in which he explores the conflicted nature of his own phenomenal success. One can only imagine the nightmarish existence endured by celebrities of any kind, let alone those (like Allen) who appear to long for a semblance of privacy and normalcy in their everyday lives; in Stardust Memories, Allen is able to show us in satirical detail exactly what it’s like to be confronted on a daily basis by “everyone under the sun who needs a favor”, ranging from a look at one’s fledgling script, to endorsement of worthy causes, to simple yet incessant autograph requests. (And, to Allen’s character’s credit, he handles these requests remarkably graciously, if with an obvious level of underhanded dismissiveness.)

Meanwhile, the bulk of the narrative revolves around the typically tortured romantic existence of Allen’s alter-ego, Sandy Bates, who — much like Michael Caine’s adulterous accountant in Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) — seems to secretly desire a troubled female companion who “needs” him, rather than a confident and mature mother-figure (the latter embodied here by Barrault, and in Hannah… by Mia Farrow).

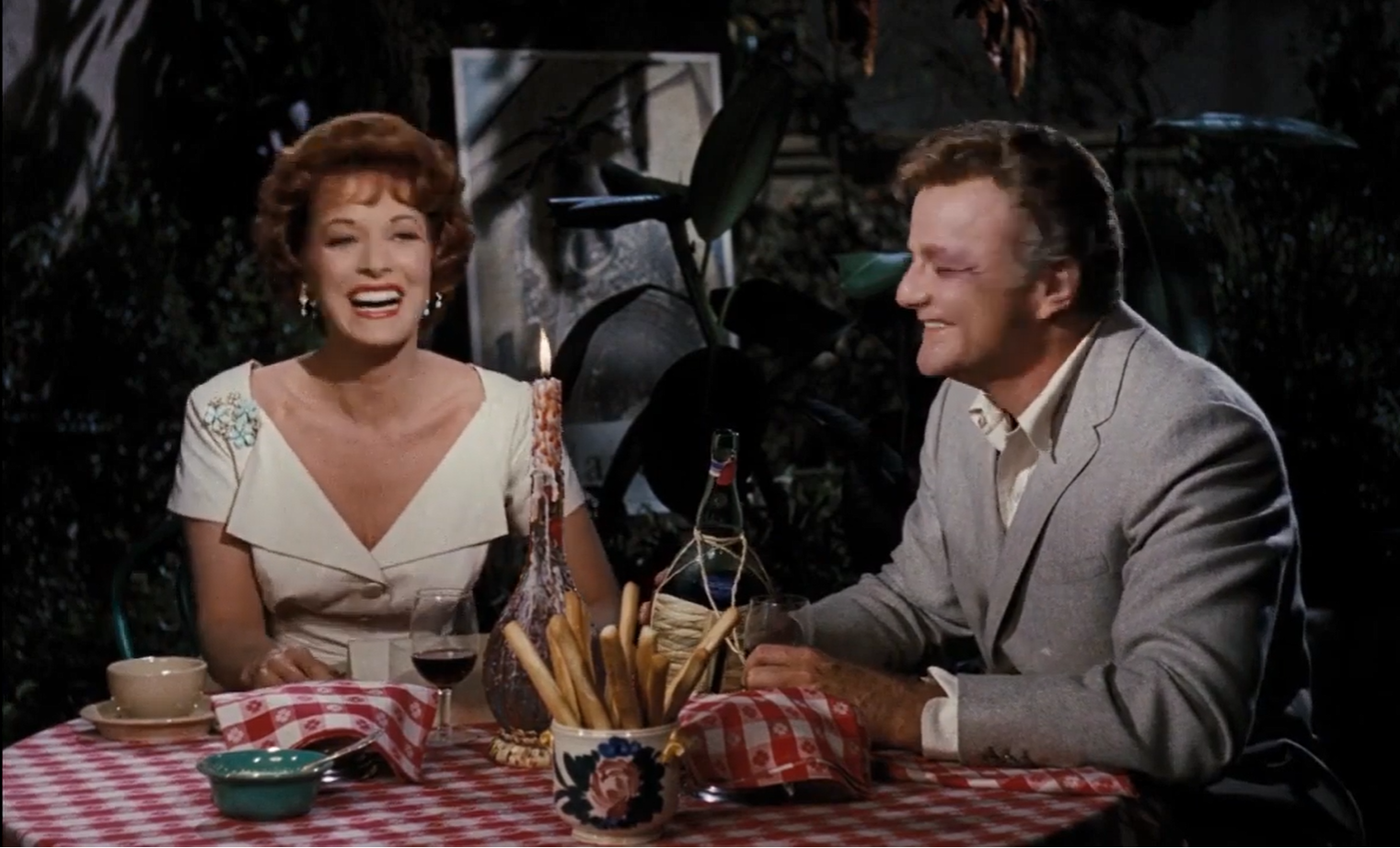

Barrault, Rampling, and Harper are all fine in their respective roles:

… and Gordon Willis’s b&w cinematography superbly highlights Bates’s stylized existence. (It’s difficult to miss the humorously outsized “portraits” of torture decking the apartment walls of this man who’s “obsessed with world suffering”.)

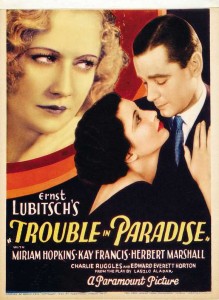

To that end, Peary rightfully points out the obvious connections between this film and Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels (1941) in its “conclusion that those who have comic gifts… should present comedy to the world… whereas others should tackle serious themes”.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Gordon Willis’s cinematography

- Effectively stylized art direction and sets

Must See?

Yes, as one of Allen’s most personal and insightful films.

Categories

- Good Show

- Important Director

Links:

|