|

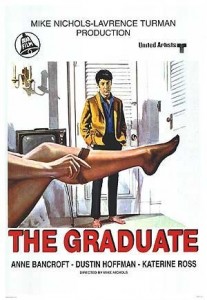

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Anne Bancroft Films

- Dustin Hoffman Films

- Generation Gap

- Love Triangle

- May-December Romance

- Mike Nichols Films

- Romantic Comedy

Response to Peary’s Review:

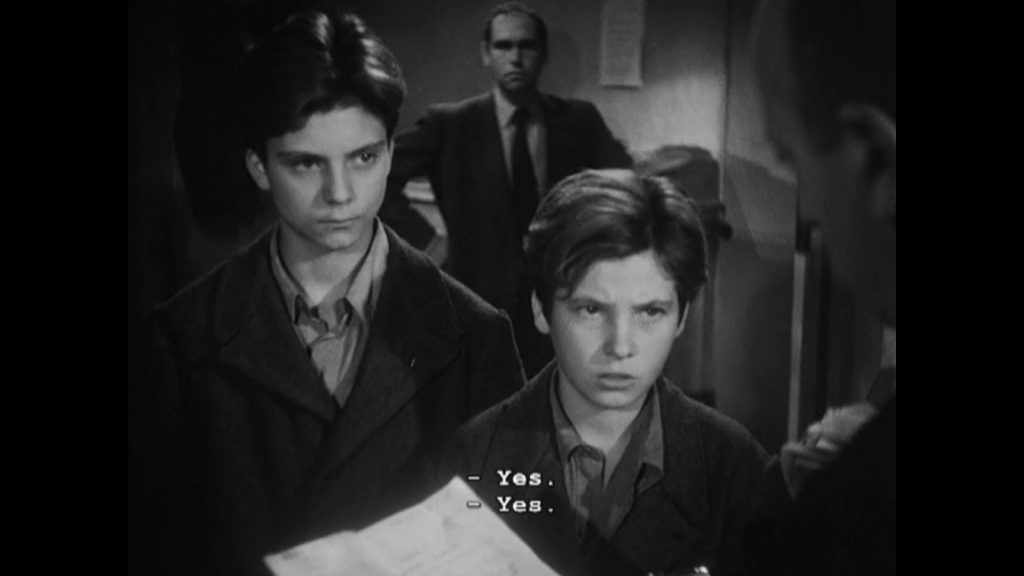

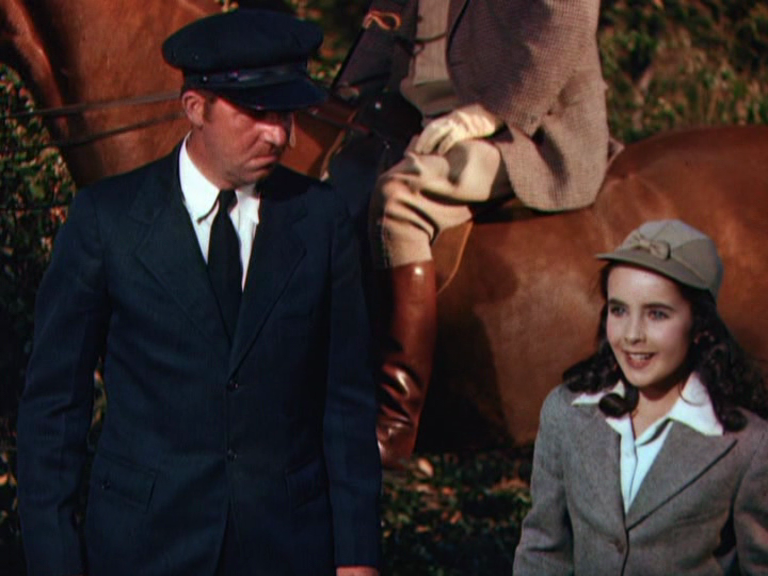

In his review of The Graduate (based on a 1963 novel by Charles Webb), Peary focuses primarily on its nostalgia value as someone who saw it “several times” the year it was released, when it was considered “the film of the year” and was “integral to everyday conversation”. He notes that “while not all of us were impressed by director Mike Nichols’s technical innovations, we were excited by his novel use of contemporary music (popular songs by Simon & Garfunkel); the provocative sexual theme; a lead character, Ben (Dustin Hoffman’s first major role), whose problems we could relate to; and a hilarious new style (for movies) of comic dialogue, in which the listener, Ben, must find words to fill in the adult talker’s long and awkward pauses.” He posits that “Nichols intentionally stops being funny at about the time Elaine enters the picture”, noting that “the humor disappears when Ben stops being passive and awkward and snaps out of his postgraduate depression”, as he “comes alive and exhibits a desperate, anarchic spirit that any young person in 1967 could identify with.” Peary concludes his review by noting that the “film is dated” but “essential to any study of film during the protest years”.

Many (including myself) would disagree with Peary’s assertion that The Graduate is “dated”, given its iconic status as a cult favorite, with countless memorable scenes and quotes:

“Are you here for an affair, sir?”

“I just want to say one word to you. Just one word… Plastics.”

“Mrs. Robinson, you’re trying to seduce me.”

“I think you’re the most attractive of all my parents’ friends.”

Peary is right, however, to point out that “the acting by Hoffman and Bancroft is super”, with “their scenes together still hold[ing] up”. Indeed, the first half of the film — during which Ben carries out his affair with Mrs. Robinson — is undeniably its funniest and most powerful, with nearly every scene packing a punch, and Nichols establishing himself as a master of sly romantic wit; Bancroft’s seduction of Hoffman will have you laughing out loud, yet simultaneously wincing at Ben’s obvious discomfort. Once Elaine “enters the picture”, it’s true that events take a more somber turn, and one can’t help regretting that Bancroft’s character eventually recedes into the background as a one-dimensional mother-bitch; but Ben’s pursuit of Elaine is ultimately what drives the film, so while we may miss Bancroft, we nonetheless remain glued to the screen, wondering how in the world Ben will salvage the mess that is his love life.

Adding to the film’s appeal is the fact that Ben remains a sympathetic character throughout the entire movie, given that he was clearly (oh, so clearly) the one seduced by Mrs. Robinson; that he tells Elaine about his affair immediately after meeting her, at which point it stops; and that he’s never anything but transparent and sincere about his intentions to put his past with Mrs. Robinson behind him. It’s also easy to relate on a personal level to Ben’s broader existential dilemma, as he contemplates how to craft a life for himself without automatically following in his parents’ footsteps; there’s nothing at all dated about that coming-of-age scenario. Finally, Nichols’ creative direction (which, unlike Peary, I do find impressive), Richard Surtees’ cinematography, fine supporting performances, and Simon & Garfunkel’s instantly recognizable soundtrack all add to the appeal of this deserved cult classic.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Dustin Hoffman as Ben (nominated as one of the Best Actors of the Year in Peary’s Alternate Oscars)

- Anne Bancroft as Mrs. Robinson (nominated as one of the Best Actresses of the Year in Peary’s Alternate Oscars)

- Katharine Ross as Elaine

- Fine supporting performances

- Creatively stylistic direction by Nichols

- Robert Surtees’ cinematography

- Richard Sylbert’s production design

- Simon and Garfunkel’s soundtrack

Must See?

Yes, of course, as a genuine classic. Nominated as one of the Best Pictures of the Year in Peary’s Alternate Oscars.

Categories

- Genuine Classic

- Noteworthy Performance(s)

- Oscar Winner or Nominee

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|