|

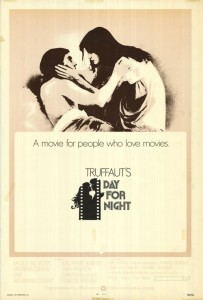

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Francois Truffaut Films

- French Films

- Friendship

- Infidelity

- Jeanne Moreau Films

- Love Triangle

Response to Peary’s Review:

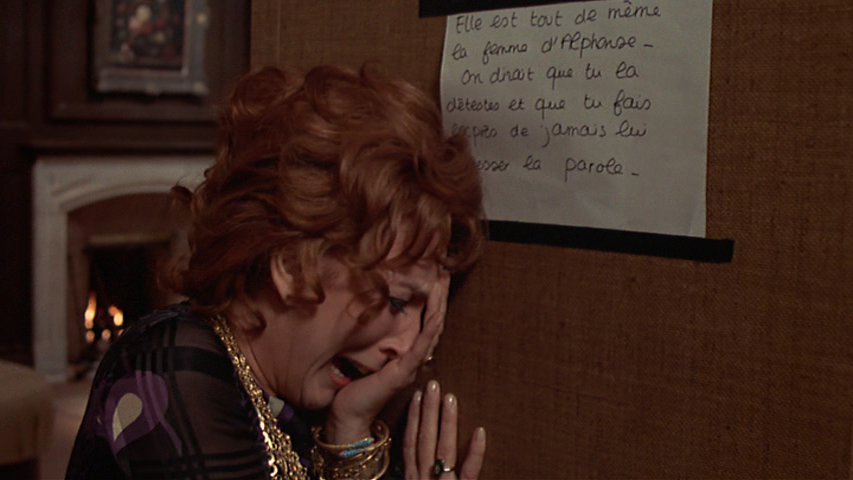

Peary refers to this “marvelous film” — a classic of the French New Wave — as Francois Traffaut’s “masterpiece”, noting that it’s “so wonderfully acted and written that it’s a pleasure to listen to”. He points out that the “sumptuous yet leisurely direction by Truffaut, music by Georges Delerue, and camera work by Raoul Coutard, particularly when panning, create an incomparably romantic ambiance”. He calls it all in all a “great film, with scenes, characters, [and] faces that will stick with you.” The bulk of his review focuses on an analysis of Catherine, “a character who is central to feminist film criticism because she embodies the contradiction present in the modern woman.” He notes that “Truffaut presents her as someone who wants to be totally independent of men, but at the same time can’t live without them and desperately needs to be placed on a pedestal, the focal point in their lives”. He argues that while her “actions… are selfish beyond reason, neither of the men nor Truffaut condemns her. In fact, Truffaut adores her”, and “feels sympathy for her as well”, while the men “regard her as not particularly smart or beautiful but as the ideal woman, who, being perfect as a child, lover, refined lady, wife, mother, companion, conversationalist, decision-maker, and catalyst to good, unusual times, is all things special to all men”.

Interestingly, while many critics seem to agree that this film is really more about Catherine than about the title characters, I remain most fascinated by the relationship that evolves between Jules and Jim, with Catherine simply serving as a mediating (and binding) influence between them. As the film opens, we’re told the accelerated story of how Jules and Jim “met”, which comes across as awfully close to a romantic infatuation:

It was around 1912. Jules, a foreigner in Paris, asked Jim, whom he hardly knew, to get him into the Art Students’ Ball. Jim got him a ticket and a costume. While Jules was hunting for a slave costume, their friendship was born. It grew as Jules watched the ball with his kind tender eyes. The next day, they had their first real conversation. Each taught the other his language and his culture until late at night. They translated each other’s poetry. They shared an indifference for money. They talked, and they listened to each other.

Of course, the story then immediately segues into the film’s decidedly heterosexual central premise — the fact that Jules “had no girls in Paris” but wanted one, and how, because “Jim had several”, he introduced a few to Jules. But the solidity and tenderness of Jules and Jim’s friendship has already been firmly established by this point; they are two of a kind, as evidenced in a charming taxi scene involving Marie Dubois’ delightfully anarchic “Therese”, who gets their names mixed up time and again, and doesn’t really mind which one she ends up spending the night with.

Even during the first pivotal turning point in the film — when Jules quietly insists to Jim that Catherine is “hers” and not to be shared — we’re pleasantly surprised to see that Jim accepts this assertion, rather than arguing or pouting. He knows that his friendship with Jules is ultimately what’s most important, and while he can’t help his own feelings for Catherine, he respectfully stays out of their romance. After a “brief” interlude of wartime (Jim admits, “Sometimes, I’m afraid I’ll kill Jules during a battle”), Jules eventually realizes that Catherine is not happy within the idyllic homelife he’s carefully crafted for their little family, and understands that he must allow Jim and Catherine’s infatuation to manifest itself physically. From this point forth, Catherine’s “selfish actions” take center stage, and we sense that we’re watching a hopeless love triangle playing itself out to a bitterly unknown end. Jules in particular remains a haunting, relentlessly intriguing presence, and Werner perfectly embodies his weary resignation.

I’ve focused my review here primarily on an analysis of the characters and their storyline, choosing just one of many interesting elements (Jules and Jim’s friendship) to explore. Equally worthy of analysis, however, is the fact that Truffaut — basing his film on an autobiographical novel by Henri-Pierre Roche — so boldly explores the nature of an “open” relationship, at a time when such a topic was rarely hinted at, let alone given center stage in a film. But what ultimately makes Jules and Jim such an enduring classic is the way in which it is told: it truly epitomizes the French New Wave, with its unconventional editing, compressed narrative structure, shifting camera styles, and thematic interest in freedom from societal constraints. While The 400 Blows (1959) remains my personal favorite among Truffaut’s oeuvre, Jules and Jim is equally relevant to any film fanatic’s understanding of this unique period in cinematic history, and is certainly must-see viewing at least once.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Oskar Werner as Jules

- Jeanne Moreau as Catherine

- Henri Serre as Jim

- Marie Dubois as Therese

- Raoul Coutard’s cinematography

Must See?

Yes, as a certified New Wave classic by a renowned director.

Categories

- Foreign Gem

- Genuine Classic

- Important Director

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|