|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

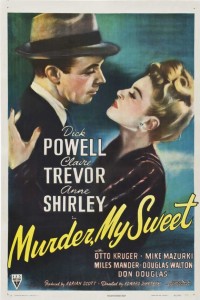

- Anne Shirley Films

- Claire Trevor Films

- Detectives and Private Investigators

- Dick Powell Films

- Edward Dmytryk Films

- Femmes Fatales

- Flashback Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

Peary argues that this “film noir classic” — “reputedly [Raymond] Chandler’s favorite adaptation of his novels” — is “director Edward Dmytryk’s best film”. He writes that while the “picture is known for its seedy characters; hard-edged, hyperbolic dialogue and narration; [and] dark, atmospheric photography”, he believes “it’s most significant because it is the one picture to fully exploit the nightmarish elements that are present in good film noir.” To that end, he notes that “because our narrator, Marlowe, spends time recovering from being knocked out and, later, from drugs in his bloodstream, he never has a clear head”, and thus “the dark, smoky world he walks through becomes increasingly surreal, indicating he is in a dream state”. He further notes that “part of the reason we feel nervous for this Marlowe is that we sense he has no more control over his situation than we do when we’re having a nightmare”. Finally, Peary comments on how effectively Powell “projects Marlowe’s vulnerability”, convincingly “making the transition from cheery crooner to hard-boiled detective”; indeed, it’s truly astonishing that this is the same actor who came to fame starring in light-hearted musicals such as 42nd Street (1933), Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933) (and 1935 and 1937), Dames (1934), and Flirtation Walk (1934).

While the storyline is dense (typical for Chandler) and requires concentration (or perhaps multiple viewings) to fully absorb, I agree with Peary that Murder, My Sweet remains a highly effective, well-acted, atmospheric noir. Powell is a stand-out:

… but the rest of the supporting cast is excellent as well, most notably the ever-reliable Claire Trevor, “coming across as sexy as Lana Turner”:

… and Mike Mazurki as “huge ex-con Moose Malloy”.

Meanwhile, Esther Howard gives a fine “cameo” performance as a boozy informant, remarkably similar to her turn several years later in Born to Kill (1947).

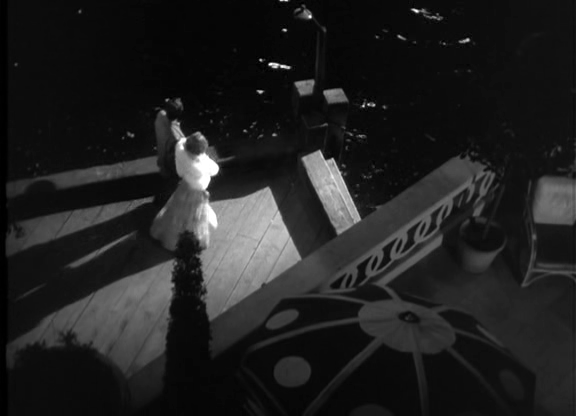

Perhaps the true co-star of the show, however, is Harry J. Wild’s cinematography (see stills below), augmented by Vernon L. Walker’s “special effects for the memorable scene in which the drugged Marlowe has hallucinations”. Remade in 1975 as Farewell, My Lovely with Robert Mitchum, but this earlier version is much better.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Fine performances

- Harry Wild’s cinematography

- The creatively filmed nightmare-drug sequence

Must See?

Yes, as a noir classic. Nominated as one of the Best Pictures of the Year by Peary in his Alternate Oscars.

Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|