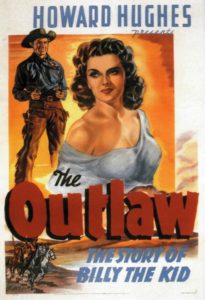

Outlaw, The (1943)

“Ever since you met him, you’ve treated me like a dog!”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Response to Peary’s Review:

Ironically, while the film does place ample emphasis on Russell’s photogenic bosom, the film is less focused on sexual dynamics between Russell and her two lovers than on, as Robert Lang notes in his book Masculine Interests: Homoerotics in Hollywood Films:

Regardless of whether one reads the relationship between Huston and Beutel as sexual or not, it’s undeniable that the real “love triangle” here is between these men (who take an instant liking to one another, for no discernable reason) and Mitchell. In his review, however, Peary simply points out that “after a while there’s too much male talk and not enough about Russell”, adding that it’s “hard to believe” the “very pretty, buxom, teenage girl in the tight, revealing dresses” is “the same actress who’d confidently sing, dance, and be funny with Marilyn Monroe ten years later in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953).” The film itself, unfortunately, is a tonally inconsistent chore to sit through. Peary writes that the “comedy and music are intrusive”, but this is an understatement: Victor Young’s score is atrociously inappropriate for the melodramatic material, which doesn’t work as a comedy. Meanwhile, the film is at least half an hour too long, and Hughes didn’t know how to elicit strong performance from his leads. While the reasons for Beutel’s limited career are contested, it seems clear to me that he was more of a pretty face than a talented actor; as noted previously, it’s challenging to understand why Huston feels such loyalty for him. Redeeming Qualities and Moments: Must See? Links: |