|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Carolyn Jones Films

- Corruption

- Detectives and Private Eyes

- Fritz Lang Films

- Gangsters

- Glenn Ford Films

- Gloria Grahame Films

- Lee Marvin Films

- Political Corruption

- Revenge

Response to Peary’s Review:

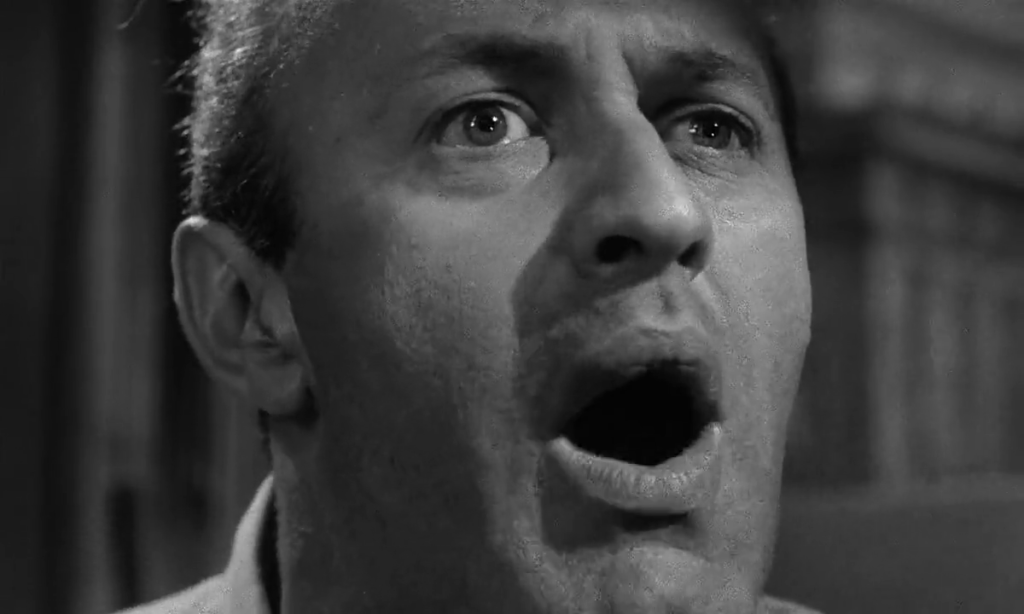

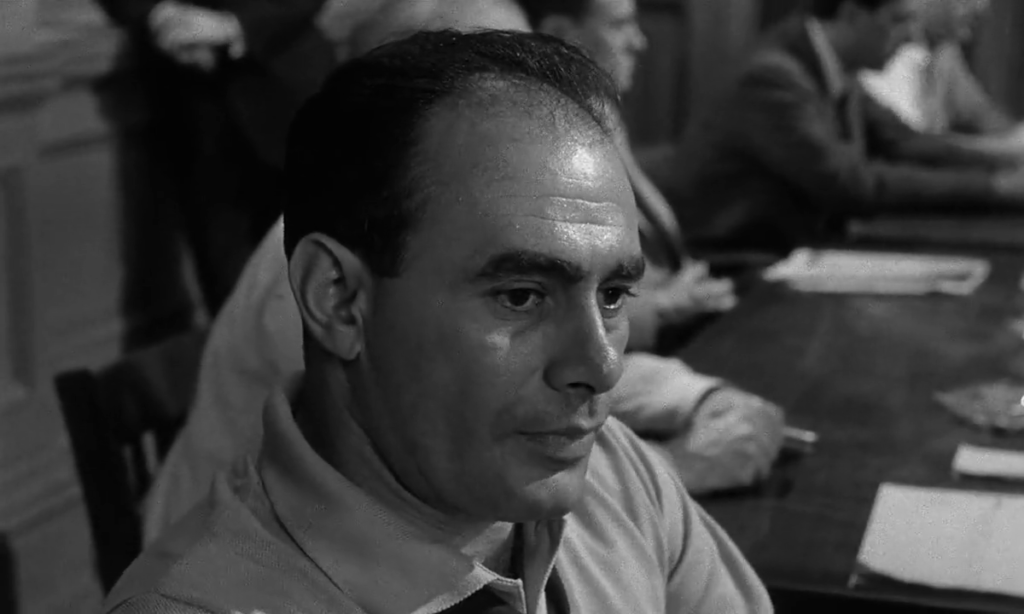

Peary writes that this “terrific Fritz Lang film” — “briskly paced, moodily photographed by Charles B. Lang, [and] brilliantly scripted by Sydney Boehm from William P. McGivern’s novel” — is “a truly exciting, political film, brimming with clever twists, sparkling touches, offbeat characters, and even scenes of genuine tenderness.” He notes that it “links hard-hitting expose films of the fifties with forties film noir,” adding that “while it coolly surveys the all-inclusive political/police corruption, it is equally concerned with the corruption of a decent man’s soul.” He writes that “among other noir elements are pervading pessimism, ferocious violence, a hero who makes one vital mistake from which there is little chance of recovery — he underestimates his opposition as much as they do him — and the intertwining traits of fatalism and paranoia”. Peary adds that “Lang sets up his usual bottomless pit over which his men must walk a tightrope”, noting that “Ford finds his allies are the least likely people in town: other people who have nothing to lose, including Gloria Grahame, who was the girlfriend of Scourby’s righthand man, Lee Marvin, until he became angry because she spoke to Ford and he disfigured her pretty face with hot coffee”. (Indeed, this shockingly brutal scene is the film’s most infamous one — though many may forget it’s “revisited” later to satisfying effect.)

To that end, as Peary writes, Grahame “does the dirty work before Ford gets a chance”, and “her charitable act purges Ford of his consuming hatred and reestablishes his faith in people.” Peary goes into greater detail about Grahame’s performance in Alternate Oscars, where he names her Best Actress of the Year and refers to her as “a great, underrated actress who was at her peak”: she had recently made a moderate impression in both A Woman’s Secret (1949) and In a Lovely Place (1950), and won a Best Supporting Actress the year before for her work in The Bad and the Beautiful (1952) in addition to co-starring in Macao (1952), Sudden Fear (1952), and The Greatest Show on Earth (1952). Peary writes that her character in The Big Heat “is one of her many sensuous, flirtatious women who are unhappy with their lives, and feel they are unworthy of the men they fall for” (i.e., James Stewart in It’s a Wonderful Life). While “she’s too good to be stuck with the brutal Vince [Marvin]”, “until she meets Bannion [Ford] she believes that he is typical of all men”, not realizing until later that “she deserves better”.

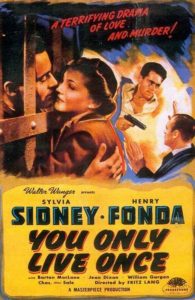

In GFTFF, Peary adds that The Big Heat is “much about territorial imperative. Notice how all the characters regard their homes or work establishments as their power bases; how the richer the home, the more corrupt its owner…; how when one person enters or merely telephones the home of an enemy, it is tantamount to an act of aggression…” He notes that “this is a vigilante film with a difference — the hero learns that going outside the law is not only wrong but the first step to becoming as bad as the enemy”. Indeed, Ford’s determined yet foolhearty actions during the film’s first half hour leave a decidedly bitter taste in one’s mouth, given the domestic tranquility we know he’s putting at risk; how can he be so dumb? It’s easier for me to contextualize this film (as noted in Peary’s Cult Movies 2 essay) within German-born Lang’s broader oeuvre of movies about characters who “have the misfortune to live in a preordained world” where “if they make the wrong decision, take the wrong fork in the road, or end up at the wrong place at the wrong time, they risk falling into a bottomless pit, a nightmare world where they have no control over their futures” — as is the case for Spencer Tracy in Fury (1936) and Henry Fonda in You Only Live Once (1937), both also starring a man “who seems to be constantly looking over his shoulder”. As Peary writes, “Dave Bannion [Ford] is a prime candidate for falling into fate’s trap”, given that “he also acts impulsively… rather than considering the possible consequences for himself and his family. It pays to be cautious in Lang’s world.”

Note: Little to no mention is made by critics of the opening scene, when Lagana’s male employee emerges on screen in a white terry-cloth robe to hand the phone to his sleeping boss — this, combined with lack of physical evidence of a wife, and the presence of numerous hunky young bodyguards, implies Lagano’s sexual preferences without highlighting them.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Gloria Grahame as Debby

- Glenn Ford as Dave Bannion

- Excellent supporting performances throughout

- Fine direction and cinematography

- Sydney Boehm’s hard-hitting script (with much credit to William P. McGivern’s source novel)

Must See?

Yes, most definitely. Nominated as one of the Best Pictures of the Year in Alternate Oscars.

Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|