|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Child Abuse

- Horror Films

- Michael Powell Films

- Movie Directors

- Peeping Toms

- Serial Killers

- Shirley Anne Field Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

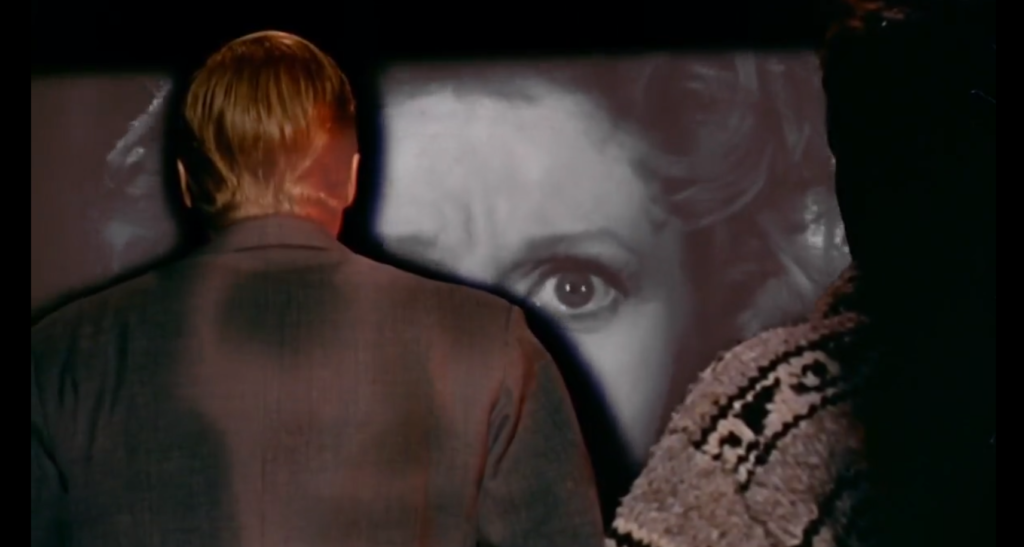

Peary writes that director “Michael Powell’s once damned but now justifiably praised cult film” is “sleazy-looking — after all, the subject is sordid — but [an] amazingly provocative picture” — one that’s nonetheless “not for all tastes”. He notes it was and is controversial in part because Boehm’s “violent acts corresponded to sexual gratification” — and “Powell doesn’t try to be subtle” given “the long, sharp, hidden knife that is attached to Boehm’s camera [which] emerges just before his murders”. He further adds that Boehm’s case is “peculiar” given that killing is not enough; instead, he must project “the woman’s dying expression on the wall in his room” in order to seek satisfaction. Peary (like many critics) points out that Powell “is making us identify with Boehm because we share his voyeuristic tendencies — like him, we are entranced by horrible images on the screen: murders, rapes, even mutilation,” and thus “we are in complicity with filmmakers who place brutal, pornographic images on the screen for our gratification.”

Hold it right there: I most definitely do NOT enjoy seeing such things on screen, and while I know many do, it’s sloppy to lump together all movie lovers (indeed, all humans) in this fashion. Peary adds that “if the voyeur is guilty of violating one’s privacy, then Powell sees the filmmaker as being guilty of aggressive acts not unlike rape (where you steal a moment in time, and a person’s emotions, that the person can never have back).” I’m ultimately more in agreement with Vincent Canby’s 1979 review of the re-released film (restored by Martin Scorsese), in which he states:

What seems to fascinate Peeping Tom‘s new supporters is Mr. Powell’s appreciation of the idea that the act of photographing something can be an act of aggression, of violation (of the object photographed), an idea shared by some film makers (including Alfred Hitchcock in portions of his classic Rear Window, made in 1954), professional thinkers and members of certain other primitive tribes … As interested as I am in films, the properties of the movie camera are not, for me, a subject of endless fascination. The movie camera is not magical. It’s a tool, like a typewriter.

Indeed, filming someone is not rape, and watching filmed images does not equate taking away anything from the person on screen, especially not in a violent fashion.

Back to Peary’s review (excerpted from his lengthier essay in Cult Movies), he points out that “the villain of the picture is not Boehm but Boehm’s dead scientist father (played by Powell in a flashback) who used his young son as a guinea pig, terrifying him and filming him to study the effects of fear on the boy’s nervous system.” (Ick; the fact that this is openly put forth in a film from this era is remarkable.) Peary reasons that Boehm “figures that since his scientist-filmmaker father in effect ‘murdered’ him, his guinea pig, then he, also a filmmaker-scientist, has a right to kill human beings when continuing Dad’s experiments.” This psychoanalytical explanation makes as much sense as any other; what’s indisputable, however, is how badly damaged Boehm is — which leads one to wonder why all the women around him (other than blind Audley) aren’t better at picking up on the rather obvious creepiness he projects from every pore. He lacks even Norman Bates’ attempts at charm and wit, and one can’t help feeling like the women he’s imperiling (specifically Massey) are out of their minds for hanging out with him.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Powerful direction by Powell

- Otto Heller’s cinematography

- Brian Easdale’s score

Must See?

Yes, for its cult status.

Categories

Links:

|