|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Alan J. Pakula Films

- Dustin Hoffmann Films

- Jason Robards Films

- Journalists

- Martin Balsam Films

- Ned Beatty Films

- Political Corruption

- Robert Redford Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

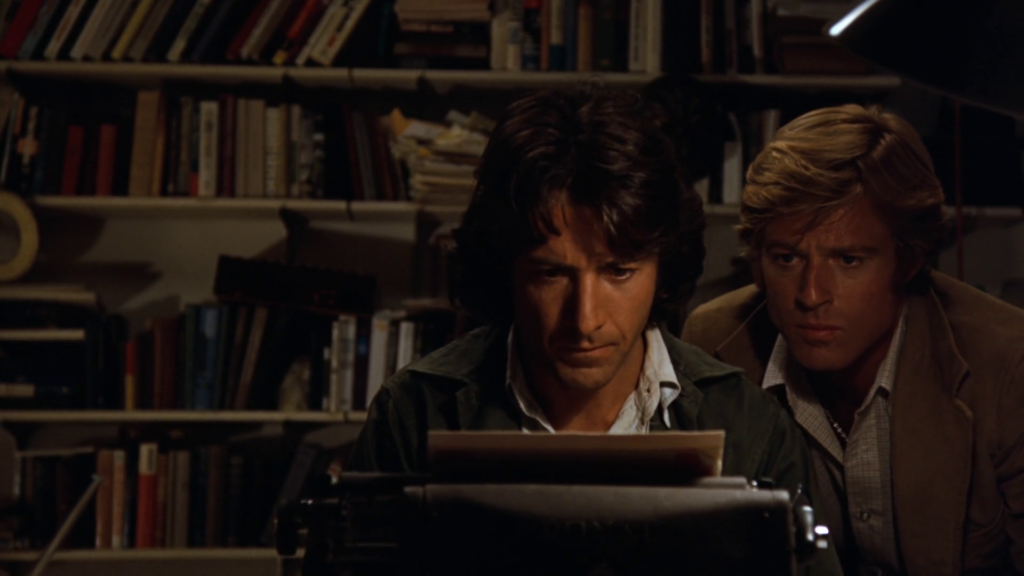

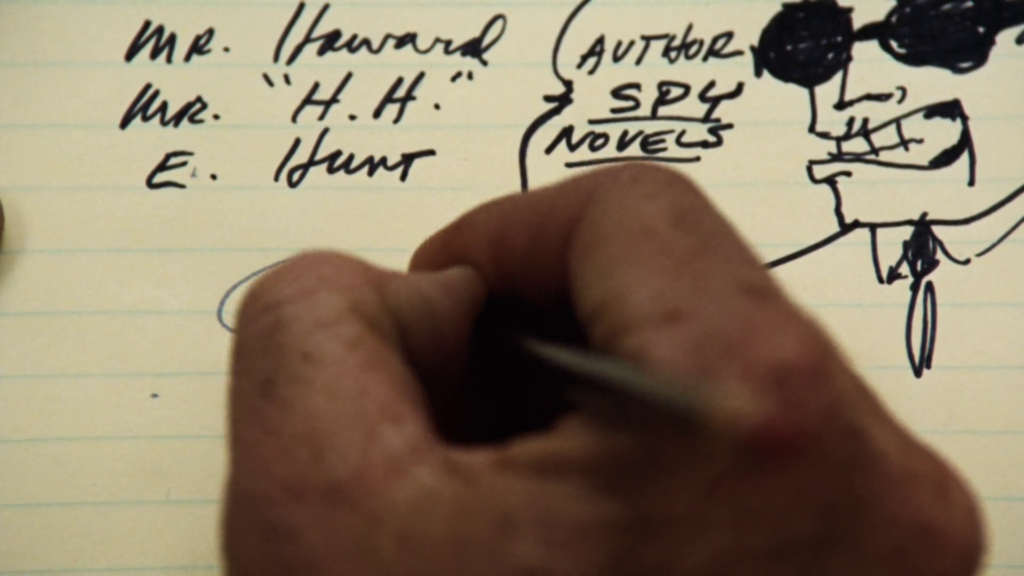

Peary asserts that this “award-winning adaptation of the best-seller” that led “to President Nixon’s resignation” is “one of the cagiest films ever made.” He notes that “we are enthralled” even though “not much happens,” given that “major discoveries by the two investigative reporters are few and far between” — and, “as he had done with The Parallax View, [director Alan] Pakula steeps his film in paranoia.” Peary describes Pakula’s directorial style thus:

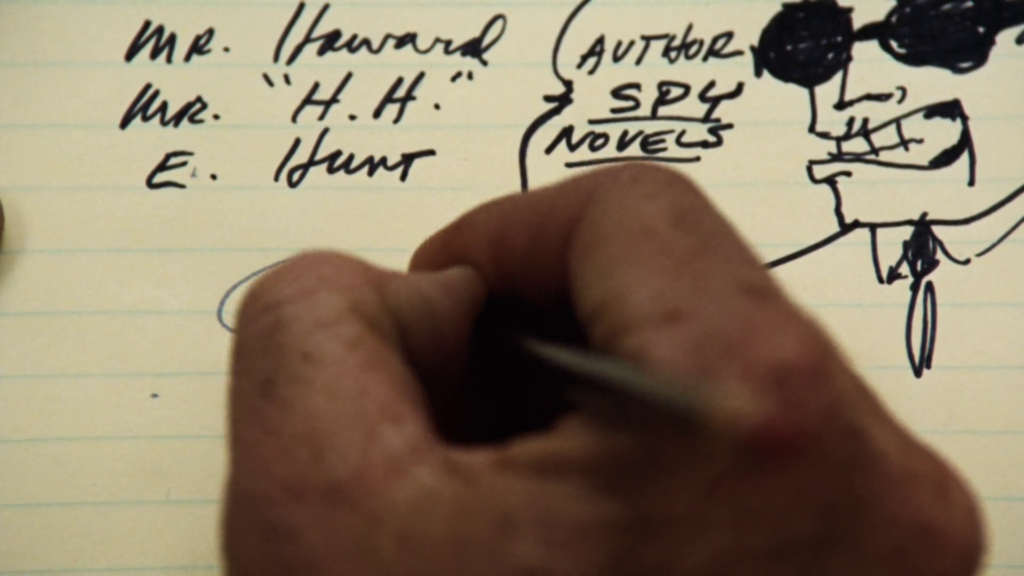

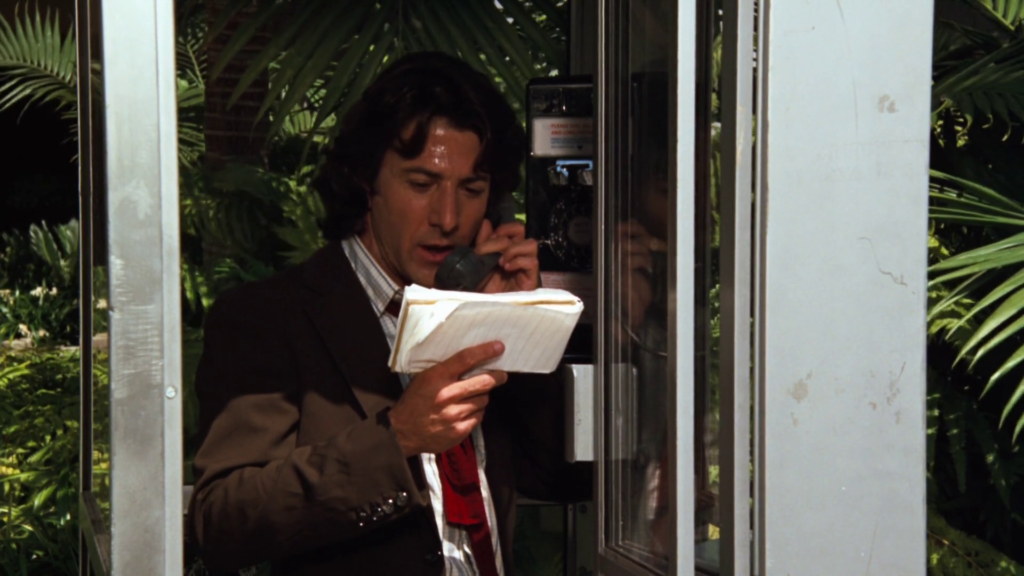

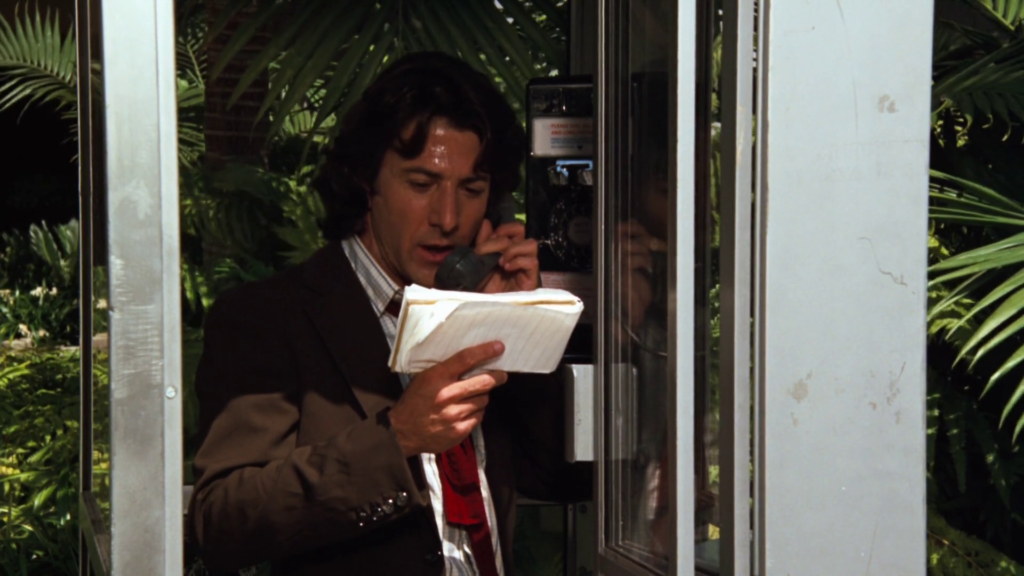

“Woodward and Bernstein are shown in close-up as they talk to strangers on the phone, trying to wangle information out of them. They sweat slightly as they bluff prior knowledge about what the people are divulging or insinuating — they worry that the people will stop in mid-sentence and question their right to ask such things. Because we don’t see the people the reporters speak to, they naturally become mystery figures — Pakula gives them nervous, reticent, suspicious deliveries so we feel they all have something to hide” [they do!] “or that they’re the types who might arrange for something nasty to happen to the hard-pushing reporters.”

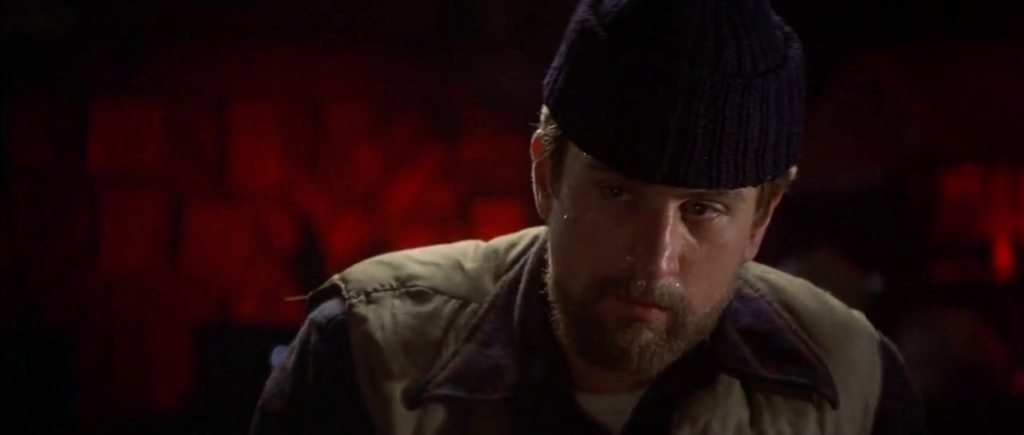

Peary argues that “if Pakula had moved the camera back from the reporters and directed the actors on the phone to speak in friendly, cooperative tones (using the same dialogue), we would feel no suspense.” Meanwhile, he notes that if Pakula “didn’t repeatedly show our reporters going alone, mostly at night” (meaning, after working hours, when people are likely to be home?) “to the doors of people who don’t want to speak to them or who are reluctant to reveal all they know” (hmmmm, I wonder why?) “or, as in Woodward’s case, meeting his contact ‘Deep Throat’ in an underground garage so dark we can’t see faces, we wouldn’t think that our two heroes are so vulnerable (or brave).”

I’m not quite sure what Peary is getting at with these criticisms, nor what he means when he says, “Near the end we are told that they are in danger — we felt it all along — but nothing comes of this. Indeed, none of the paranoia we feel throughout the film is justified.” I disagree. Bernstein and Woodward are authentically concerned — as they should be — about their jobs (not to mention the reputation of their esteemed newspaper) being on the line; and when dealing with high-level politicians and their lackeys, I don’t think there’s such a thing as being too cautious (or, frankly, too paranoid). All the President’s Men is inherently dramatic given what the reporters end up uncovering, which impacted nothing less than the course of American history. Peary does concede that the “acting is excellent, particularly by Jason Robards, Jr., who won a Best Supporting Actor Oscar as the Post‘s managing editor, Ben Bradlee”

… and that “another plus is that we get a sense of the inner workings of a newspaper and how individual reporters pursue a story (i.e., phone calls, legwork, paperwork).”

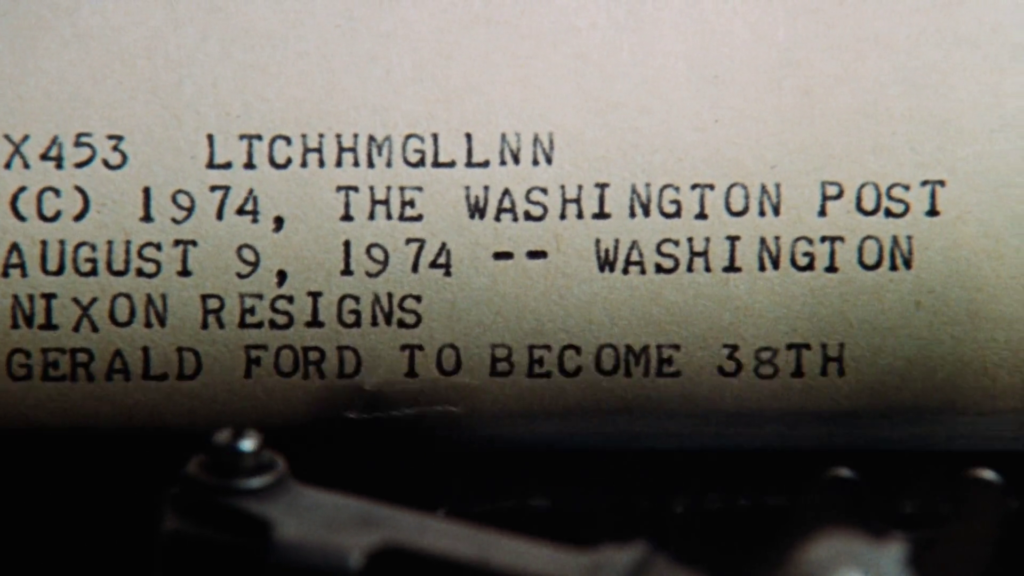

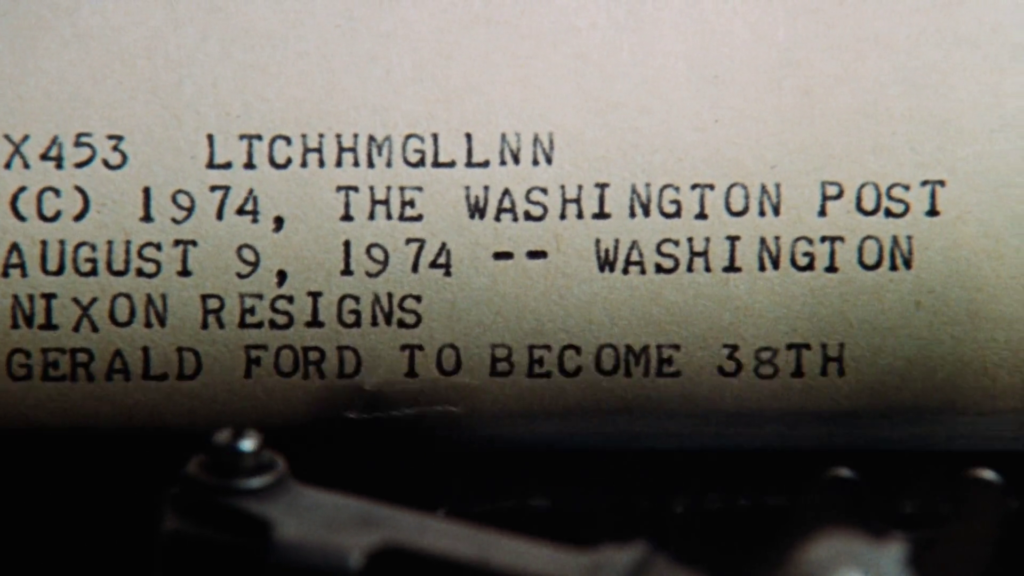

Peary’s strongest complaint seems to emerge near the end of his review, when he notes that “Woodward and Bernstein are shown to be manipulative, driven, willing-to-fib reporters — likable but not all that sympathetic. They seem to favor getting their Pulitzer-caliber story, without concern for what that story will mean to the country.” (This echoes Peary’s similar criticism about Claude Lanzmann’s relentless investigative work for Shoah.) Peary argues that the “end of [the] film comes too early in the Watergate story and leaves us hanging — which is also the major problem with the book,” but once again, I disagree; the final typewritten sequence in the movie perfectly bookends the way it opened (on a plain piece of paper), adding a sucker-punch conclusion to the men’s work:

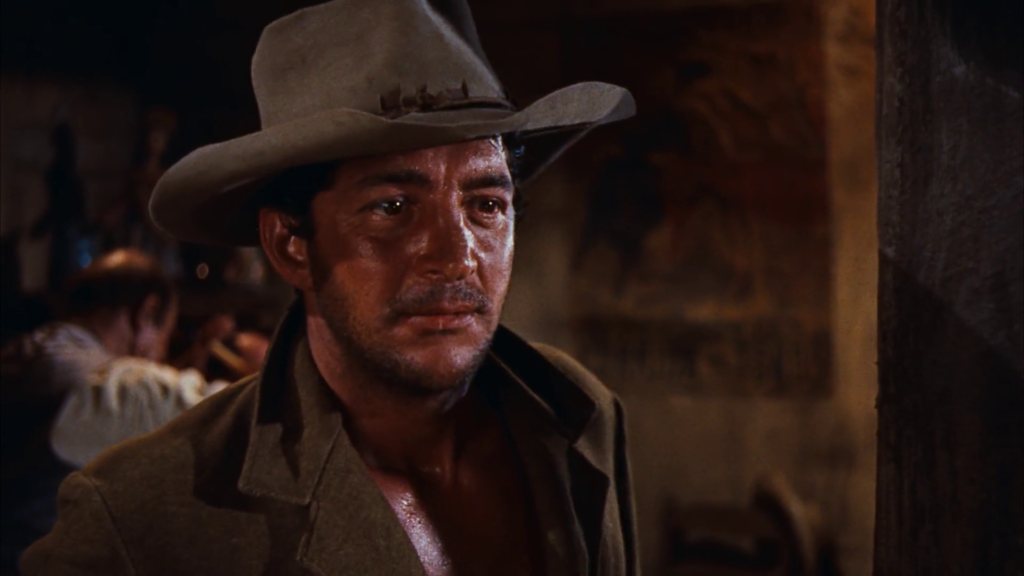

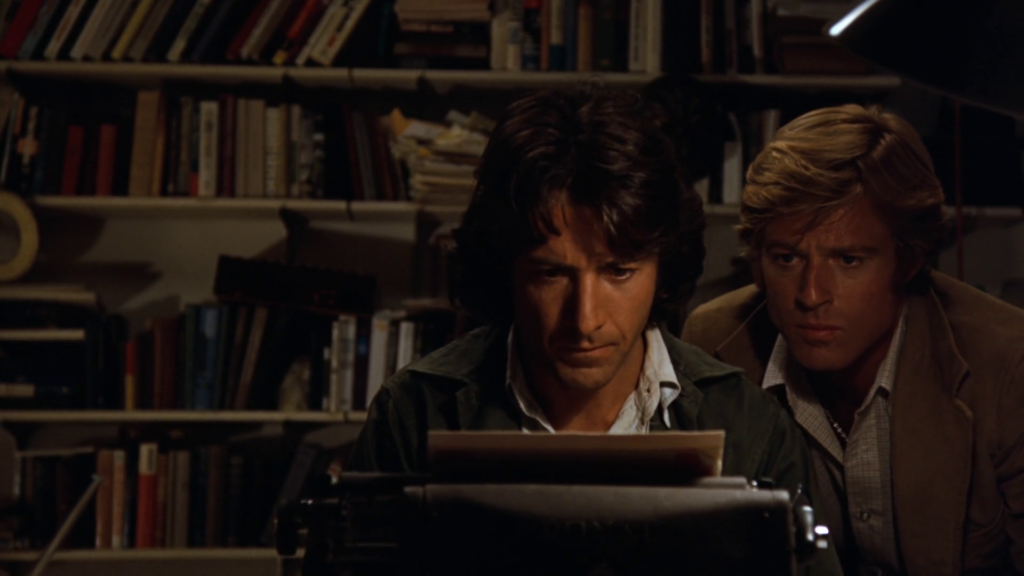

Meanwhile, I’m a fan of both Hoffman and Redford’s performances (not highlighted in Peary’s review), and am impressed that we stay so engaged in their travails despite knowing how things turn out. This one remains worth a look.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Fine performances by the cast

- Gordon Willis’s cinematography

Must See?

Yes, as a still-engaging classic.

Categories

- Genuine Classic

- Oscar Winner or Nominee

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|