Greetings to my fellow Film Fanatics,

I’ve never used FilmFanatic.org to blog about my ongoing progress with the site, or to share my thoughts in general on watching and writing about the unique niche of “pre-1986 must-see films”, but I’ve thought about doing so for quite a while — so, here I finally am.

Since posting my first brief review on March 4, 2006 (of Jean-Jacques Beineix’s Moon in the Gutter), I’ve added 1,405 reviews to the site — which is roughly one-third of the 4300 titles included in GFTFF (for those who care to keep track). At this rate, it should only take me another 10 years or so to complete this project! Not that completion is the goal per se… By the time I finish (re)watching and writing about all the titles in Peary’s book, I’ll probably be ready to visit and/or comment on many of them again. Or I may finally get serious about diving into my ModernFilmFanatic.org site, which I’ve had to put on hold for now… In addition to maintaining this site, I’m married with two little kids and a full-time job, so time and energy are severely limited!

(I’ll post more on this topic another time, but I actually find that having a really busy life with limited time for movies helps me appreciate them all the more. I may complain quietly to myself on a daily basis that I wish I had more time to devote to the site, but ultimately, a diet of pure cinema has never been a healthy choice for me; hence, my decision to enter into a non-film-related career. Peary himself admits to burning out after writing GFTFF, which should be taken as a cautionary warning of some kind.)

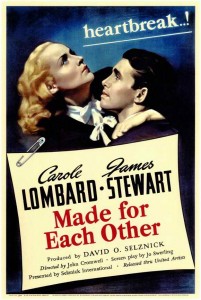

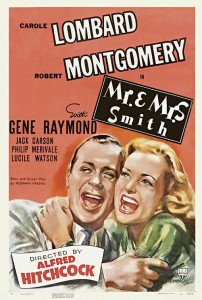

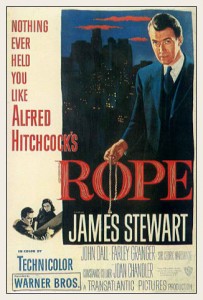

At any rate, recently I’ve found myself watching and posting on movies in thematic “clusters” — I’ll suddenly notice I’ve been watching a bunch of a particular actor or director or producer’s films, for instance, and decide I might as well finish watching all of them to really get a sense of the gestalt of that particular person’s work (as selected by Peary, and only up until his 1986 publishing deadline, of course). My most recent attempt has been to finally finish up rewatching and posting on all of the 41 Hitchcock films included in GFTFF (I only have 7 left at this point). He’s probably my favorite director (if I had to choose), and it’s been a true pleasure to revisit the majority of them. 1,001 Movies You Must See Before You Die (a well-meaning but horribly pretentious and flawed book, btw, yet nonetheless the one used by most modern film fanatics as their go-to checklist, so I continue to reference it) lists no less than 18 of his titles, which is impressive, and speaks (I believe) to their enduring power.

In contrast, I also recently watched nearly the entire Universal Studios Frankenstein series — a project it made sense to attempt in one go, given that serialized films like this really are best reviewed in comparison with one another, and at least relatively in order (to get a sense of their chronological progression). However, while there are very few GFTFF-Hitchcock titles I’ve voted “no” on (and even those “no” votes are, I believe, worth a one-time look by serious film fanatics), Peary’s inclusion of ALL the Universal Frankenstein titles in his book is an example of what I refer to repeatedly as his sense of “completism” — a symptom either of his inability to decide which of the many titles are must see (so why not include them all??), or his genuine belief that any true film fanatic will WANT to have seen all the titles in a particular “series” or franchise (no longer really a sustainable choice, given the wealth of new titles produced all the time — a film fanatic only has so much viewing time to spread around!). Since beginning the site, I’ve been working hard to sift through all such titles and make critical decisions on behalf of my fellow film fanatics — which, of course, you can and should feel free to disagree on.

Just as mysterious to me is Peary’s random inclusion of certain titles by a particular performer and/or director — say, Danny Kaye or Jerry Lewis — to the exclusion of others. While he nearly always includes all the “big name” titles of a star (for obvious reasons), I’m puzzled why, for instance, Peary includes Lewis’s lame The Sad Sack in his book when there are other “bigger name” titles he could have chosen to include instead, if he really wanted to beef up the number of Lewis offerings (which he DIDN’T need to do!). At any rate, ultimately this kind of thing comes down to personal taste — and I’ll admit that a tiny part of me is secretly tickled by Peary’s blatant favoritism. He’s not afraid to call a personal favorite a Must See title — and while I may fervently disagree with his choices, he’s at least (covertly) admitting that subjectivity is an inherent element in any such daunting undertaking.

I’ll continue to post occasional “check-in” blog entries in future weeks and months, on various topics that have occurred to me — including:

* how I decide which film to watch and review next (partially touched upon here)

* how my thinking about which films are must see or not has evolved over the years (and continues to evolve)

* my summative thinking on the oeuvres of various actors or directors whose Peary-listed work I’ve finished reviewing (including Jerry Lewis, Danny Kaye, Abbott and Costello, and others)

Back to viewing and reviewing! Thanks for reading.

–Film Fanatic