|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Biopics

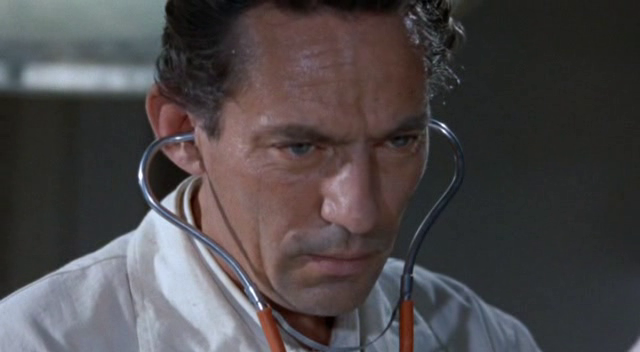

- Frank Morgan Films

- Luise Rainer Films

- Marital Problems

- Myrna Loy Films

- Showgirls

- Vaudeville and Burlesque

- William Powell Films

Review:

Referred to by TV Guide as “three hours of lumpy, overcooked pudding”, this infamously undeserving Best Picture winner may, as DVD Savant posits, set “new records for whitewashing a famous personage”. In his Alternate Oscars book, Peary refers to it as “an endless picture… with some of the most boring musical numbers imaginable”, noting that “even a number with a hundred chorus girls in their underwear is numbing”. DVD Savant is similarly no-holds-barred in his scathing review of the film, in which he asserts, “I’m assuming what we see here is almost a total fantasy”, given that:

“MGM’s Ziegfeld [apparently] had no faults, only the impish need to upstage his pompous pal played by Frank Morgan. He loved all women but had no affairs, and was essentially faithful to his first wife (doubtful) and devoted to his second (entirely possible). He’s that kind of rogue who’s forever broke but somehow living a permanent life of luxury, skating on his personality and promotional talent.”

Indeed, we ultimately learn frustratingly little about this larger-than-life historical figure, a man who had only been dead for a few years at the time of the film’s release, and whose widow (Billy Burke) was notoriously invested in ensuring that her beloved husband’s name not be sullied in any way. There actually seems to be an overarching fear of placing any of the characters here (most still alive) in too bad a light — with the exception of Virginia Bruce’s “Audrey Dane” (a stand-in for Ziegfeld’s real-life lover, Lillian Lorraine), who bears the brunt of the narrative’s bitchiness factor.

The real aim of the film, it seems, was to tap into audience members’ nostalgia for the Follies, since at that time, they were not all that far removed from people’s lived experiences; for today’s viewers, however, what passed as entertainment back then is simply puzzling in its unintentional banality. DVD Savant asserts that “most of the big numbers here are ugly in the extreme”, and that “grandiosity has never seemed so hollow” — sentiments which accurately capture my own feelings when watching one overblown production piece after another, all seemingly meant simply to wow audiences with sheer spectacle. But there’s very little “there” there. Other than a snippet of Fanny Brice singing “My Man”, and a pre-Wizard of Oz Ray Bolger performing a dance that shows ample evidence of why casting agents thought he would be perfect playing a limp-limbed scarecrow, the numbers really aren’t that memorable. Indeed, by the final one, I found myself simply distracted, with thoughts running through my head like, “Oh — there’s a woman in a drum majorette outfit dancing in front of a row of trained dogs. How strange.”

Luise Rainer’s Oscar-winning performance as Ziegfeld’s first wife, Anna Held (a.k.a. ‘The Viennese Teardrop’), is a primary reason film fanatics may be curious to see this movie — especially given that Rainer won an unprecedented second Oscar in a row the following year (for The Good Earth), then virtually disappeared from movies altogether; she’s a bit of an enigma. With that said, while she “had beauty, charm, and talent” (as stated by Peary in Alternate Oscars), audiences today will likely concede that “her characterization of Held as a sweet, emotional, indecisive, and insecure outsider wavers from being adorable to being irritating”. Peary further argues that her “celebrated phone call scene in which [she] pretends to be happy when she congratulates Ziegfeld on his [second] marriage… is a shameless scene that would have gotten an audience reaction no matter which actress played it”.

This is all true — and yet I’ll admit to finding myself somewhat transfixed whenever Rainer was on-screen; she did possess a strangely magnetic (if, indeed, mildly irksome) personality, and it’s a shame her cinematic career was so erratic after this.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Rainer’s Oscar-winning performance as the petulant but winsome diva Anna Held

- Fanny Brice singing (part of) “My Man”

- Ray Bolger’s “elastic” dancing routine

- Typically outrageous Follies costumes

Must See?

No, though most film fanatics will likely be curious to check it out once just for its dubious relevance as an Oscar winner. Listed as a film with Historical Importance in the back of Peary’s book.

Links:

|