Reflections on Must-See Films From 1965

I’m back for another reflection on a particular year in cinema! As a recap, I’ve already shared my thoughts on must-see titles from 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963, and 1964 — and I’m now ready to discuss my take-down on titles from 1965.

Interestingly, this year holds my lowest percentage of must-see titles so far. Out of 73 movies, I’m only voting 19 (or 26%) must-see. Below are just a few highlights from this year in cinema, which offered up plenty of darkness (literally — most are in b&w) on screen; however, I’ll begin my overview with a notable exception to that tendency.

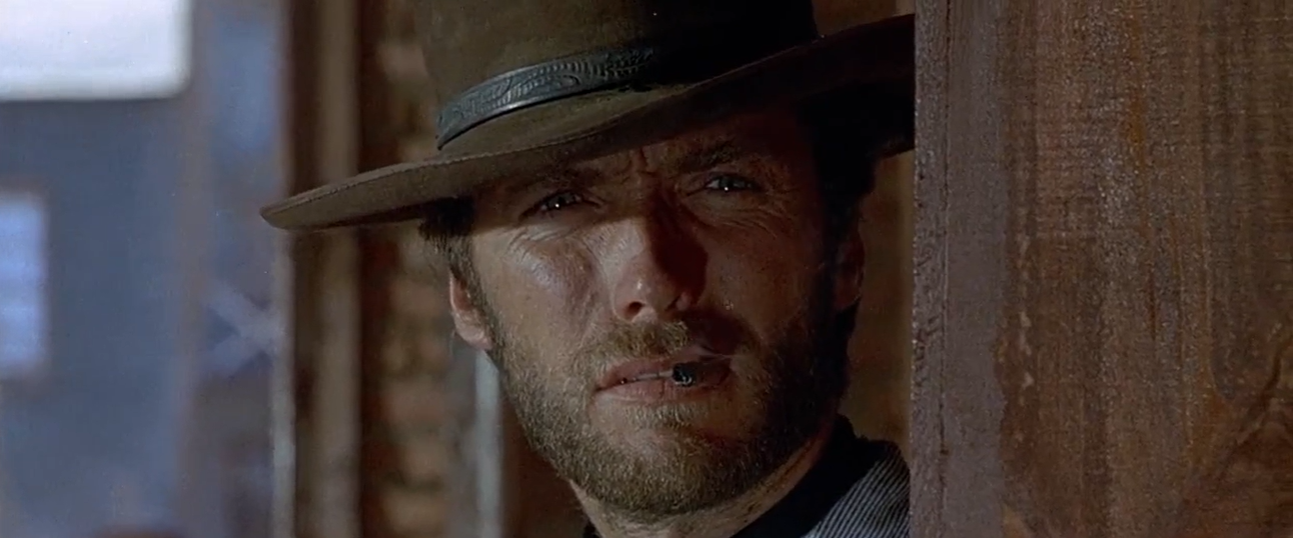

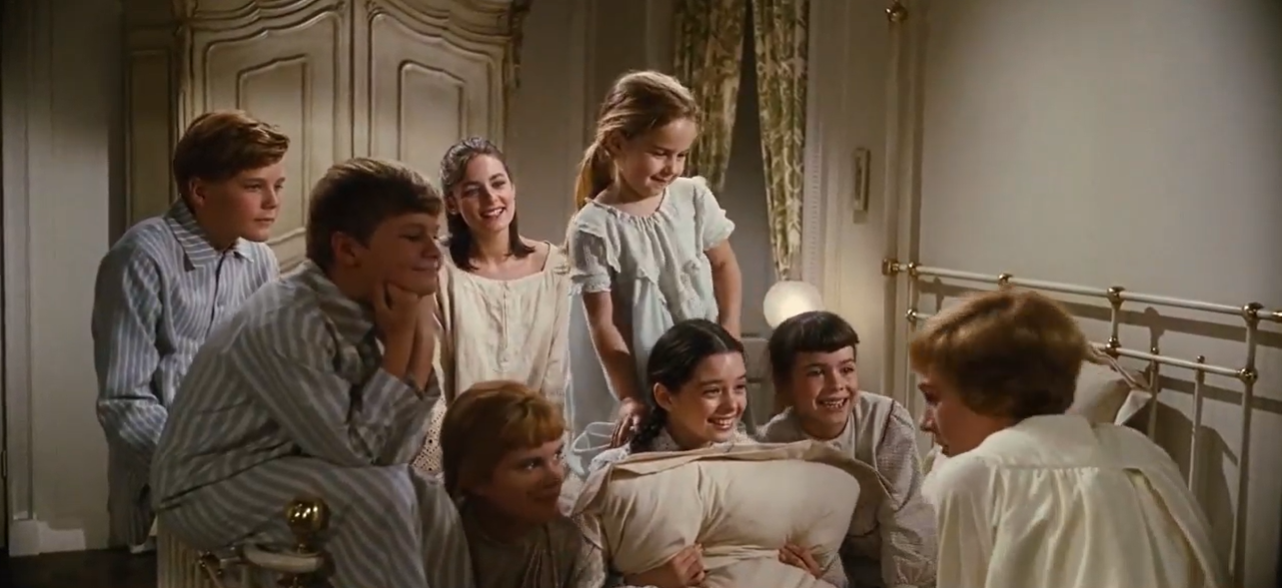

- I’m a huge fan of Robert Wise’s Oscar-winning musical The Sound of Music, which is not to everyone’s tastes but has delighted me for years. Julie Andrews’ performance remains preternaturally compelling, and as I noted in my review: “The use of authentic Austrian/German locales — including the iconic opening shots on verdant hillsides — helps to open up the [original Broadway] play enormously,” turning “the entire affair into a wonderfully picturesque adventure.”

- Of the 19 must-see titles from 1965, seven are in a language other than English, with two (discussed below) in Italian, two in French (see here and here), and three in Czech. From the latter (which also includes Milos Forman’s Loves of a Blonde and Zbynek Brynych’s The Fifth Horseman is Fear), the Oscar-winning flick The Shop on Main Street — a film “about the absurdity of war, politics, and discrimination” in which “we are clearly able to see the insanity of the social upheaval creeping across Europe” — stands out above them all.

- Another powerful foreign title is Marco Bellochio’s debut feature Fists in His Pocket, about a young man who “decides to relieve his older brother… of their dysfunctional family by gradually killing everyone — including himself — off.” (!) In my review, I note that watching this movie — which comes across as “part black comedy, part character study, part horror film” — is like viewing “a train wreck in slow motion”: we remain “fascinated yet unable to look away,” particularly given Lou Castel’s “powerhouse performance” as a man suffering from “depression, grandiosity, and mental instability.”

- Speaking of memorable performances, it’s impossible to forget Rod Steiger’s leading role in Sidney Lumet’s bleak holocaust-survivor film The Pawnbroker. As I note in my review, “Viewers must prepare themselves for relentless agony as we watch a deeply broken man perpetuate his own horrors onto others through grim apathy and misanthropy.” This film is well worth a one-time watch — but be forewarned.

- Equally (though differently) disturbing is Roman Polanski’s Repulsion, starring Catherine Deneuve as a young French woman in London who experiences a frightening mental decline. Her performance — as well as Polanski’s ability to work atmospheric wonders within a tight budget — make this a tense psychological thriller with plenty of unexpected twists and turns.

- Peter Watkins’ fictionalized docudrama The War Game — which was “deemed too controversial for airing on BBC television, but was given a theatrical release, and received an Oscar for best ‘documentary’ in 1967” — offers up a “hypothetical vision of a post-apocalyptic nightmare — including lack of sufficient food or medicine, military rule, and hideous physical symptoms.” As I note in my review, it “remains just as powerful today as it must have been [decades] ago, when the threat of nuclear war was even more [?] imminent.”

- There are several cult classics from 1965, with perhaps my personal favorite being Elio Petri’s “cleverly conceived, visually stylish” (it’s in color!), “smartly scored,” Italian-language sci-fi flick The 10th Victim — about “a futuristic society which allows individuals to join a human hunting game.” Ursula Andress (the huntress) and Marcello Mastroianni (her prey) are perfectly cast as the cat-and-mouse leads, with Andress a particular revelation as she “delivers a nuanced, smart, humorous, even heartfelt performance, all while looking as incredibly gorgeous as always.”

- Another noteworthy cult flick is Russ Meyers’ inimitable Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! — which is the only Meyers film (out of all twelve listed in GFTFF) I tend to remember with much interest thanks to “its utterly unique stars…, its unforgettable title, and its striking imagery.” My review synopsis gives you a sense of how bizarre this flick is, if you somehow haven’t yet seen it (or would like a refresher):

“When three go-go dancers — Varla (Tura Satana), Rosie (Haji), and Billie (Lori Williams) — go drag racing in the desert, Varla ends up killing the boyfriend (Ray Barlow) of a bikini-clad girl (Susan Bernard) who the group then kidnaps. They end up at the home of a reclusive, secretly wealthy sociopath in a wheelchair (Stuart Lancaster) who is cared for by his two sons: a mentally slow hunk nicknamed ‘The Vegetable’ (Dennis Busch) and his brainier brother (Paul Trinka). Sex-obsessed Billie pursues Busch, while Varla attempts to bed Trinka in order to learn where Lancaster’s money is hidden, and Bernard tries to escape.”

Whew — get ready for some wild, violent, female-fueled escapades!

- Speaking of larger-than-life characters, Orson Welles’ self-professed final directorial masterpiece was Chimes at Midnight, in which he plays the recurring Shakespearean role of Falstaff — a portly knight who experiences tremendous heartbreak and betrayal at the hands of his lifelong friend Prince Hal. It’s a beautifully crafted — albeit typically “Shakespeare-ingly” dense — cinematic outing.

- Another notable film about betrayal from 1965 was Martin Ritt’s The Spy Who Came In From the Cold, which hews faithfully to John Le Carre’s source novel and offers a powerfully sobering antidote to more escapist spy fare of the Cold War era. As I note in my review: “To its credit, the film retains all the suspense of the book while both simplifying key plot points and visually opening up certain scenes. Oswald Morris’s atmospheric cinematography is top-rate, and the performances are fine across the board.”

- Finally, I want to highlight Brian Forbes’ King Rat — a haunting adaptation (of James Clavell’s novel) which is “unrelenting in its graphic depiction of the heat, starvation, despair, craziness, lethargy, boredom, and overall sense of hopelessness pervasive in [POW] camps.”

There are quite a few dark themes emerging across these recommendations from 1965: hopelessness, despair, violence, guilt, discrimination, betrayal, kidnapping, theft, duplicity, mental instability, starvation… These all seems particularly apt for the year in which Malcolm X was assassinated; Bloody Sunday occurred in Selma; American troops first arrived in Vietnam; the Watts Uprising took place in Los Angeles; and Quaker Norman Morrison set himself on fire in protest (to name just a few noteworthy events). There was a lot going on, both in America and abroad.

Thank goodness for movies, and for the opportunity to remember a few of our favorite things…