|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Donald Crisp Films

- Feminism and Women’s Issues

- Herbert Marshall Films

- Historical Drama

- Katharine Hepburn Films

- Morality Police

- Van Heflin Films

Review:

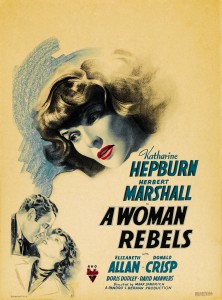

This little-seen Katharine Hepburn vehicle (based on Netta Syrett‘s 1930 novel Portrait of a Rebel) is primarily remembered as Hepburn’s third box office flop in a row for RKO studios — and unfortunately, it’s easy to see why the film failed to catch on with audiences. It’s ultimately a missed opportunity, relying far too heavily on melodramatic conventions rather than capitalizing on its more interesting feminist premise. Although Hepburn’s “Pam Thistlewaite” defiantly declares that she “has brains and intends to use them”, we see only snippets of her brave attempts to penetrate the glass ceiling in Victorian England — as epitomized in the following reactions to her attempts to seek employment in “men’s work”:

“A girl as a secretary! Why, bless my soul… I’d be the laughing stock of London.”

“Sorry, can’t be done — a salesgirl in a shop? Unthinkable. My customers wouldn’t tolerate it.”

Her character does eventually find success as an agitating feminist journalist, but unfortunately, little to no time is spent dwelling on this aspect of her life. Instead, the bulk of the narrative focuses on issues of dubious morality, as Hepburn’s “sins” of the past come back to haunt both her and her grown daughter.

With that said, Hepburn is as luminous and charismatic as always, fully embodying a role tailor-made for her sensibilities; and the Oscar-nominated period costumes she wears over the decades are a delight.

However, this one remains must-see only for Hepburn enthusiasts (and those curious to see Herbert Marshall bathing a baby while wearing an apron!).

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Katharine Hepburn as Pamela

- Fine period costumes

- Robert De Grasse’s cinematography

Must See?

No, though Hepburn fans will want to check it out.

Links:

|

One thought on “Woman Rebels, A (1936)”

First viewing. A once-must, for its place in cinema history, for Hepburn’s performance and for the direction by Mark Sandrich.

I take a more favorable view of this film – which shocks me, mainly because I generally take a dim view of Hepburn’s approach to acting in her work prior to what I think of as her breakthrough performance in ‘Bringing Up Baby’.

Here, Hepburn’s effect is much more modulated, which not only suits her but also the particular film she’s in. I can’t help but think that Sandrich was able to communicate direction in a way that other directors of Hepburn’s early work could not.

[Sandrich, by the way, was taking a break in-between directing a number of films he helmed for Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. He died fairly young (44) but seemed to have a smooth hand in filmmaking.]

For me, it’s not “easy to see why the film failed to catch on with audiences”; I find it refreshingly progressive for a film of its time. I don’t happen to think “little to no time is spent dwelling on [the feminist] aspect of [Hepburn’s character’s] life”. In fact, a genuinely thrilling moment in the film comes when Hepburn’s Pamela takes a bold step at the publication she works for: she ignores editorial doctrine and publishes an article about women that is really *about* something important to and for its mostly female readers. It is that moment that crystallizes the film’s feminist stance and moves it forward through the film.

I admit I was slightly lost before realizing that Pamela’s baby really *was* her own baby. The affair she has with Lord Gaythorne (Heflin) is so clandestine that it seems you have to pay close attention to realize that the two actually had sex.

I am fascinated by stories that serve as a window to the past, in regards to how people were constantly reminded to remember ‘their place’ (whatever that ‘place’ happened to be). Of course, anytime I’m witnessing a focus on a societal pecking order of persons, I’m more or less appalled, but fascinated nevertheless.