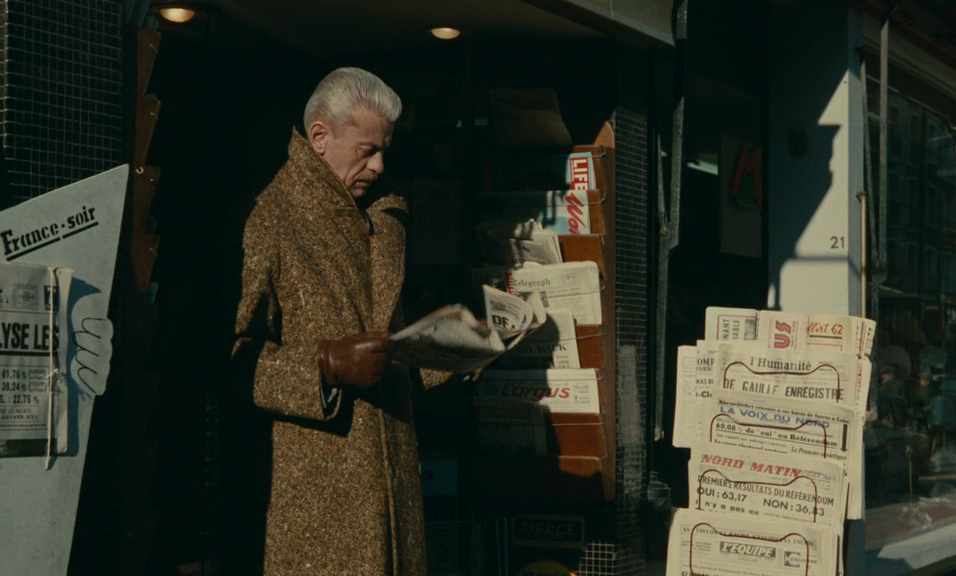

Leopard, The (1963)

“Ours is a country of compromises.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

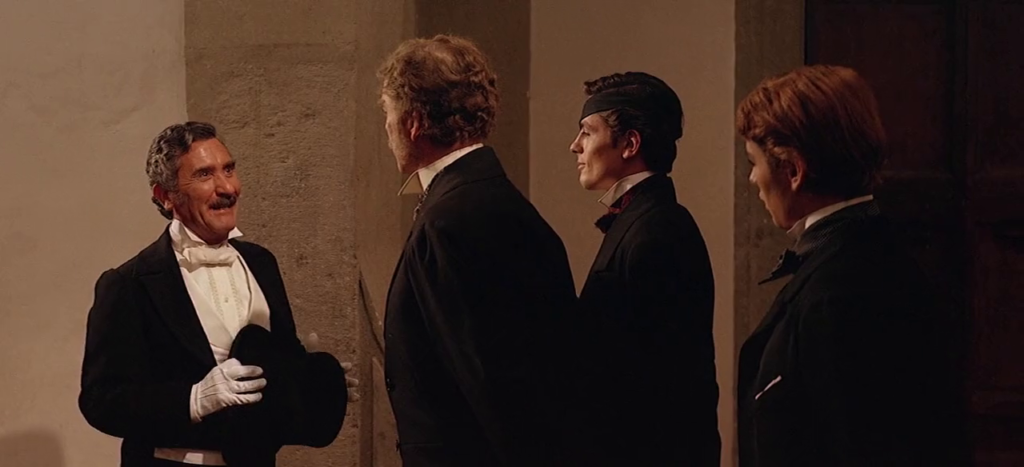

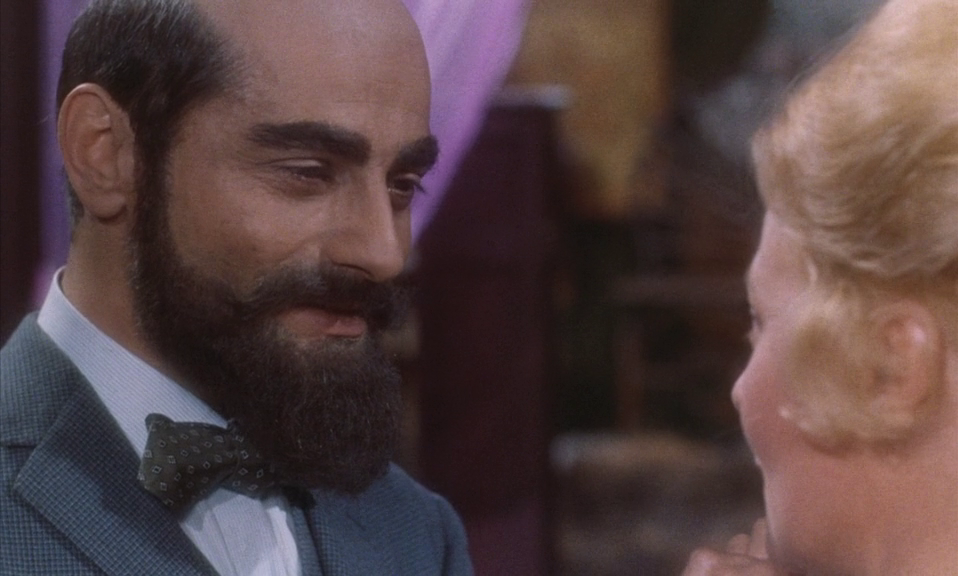

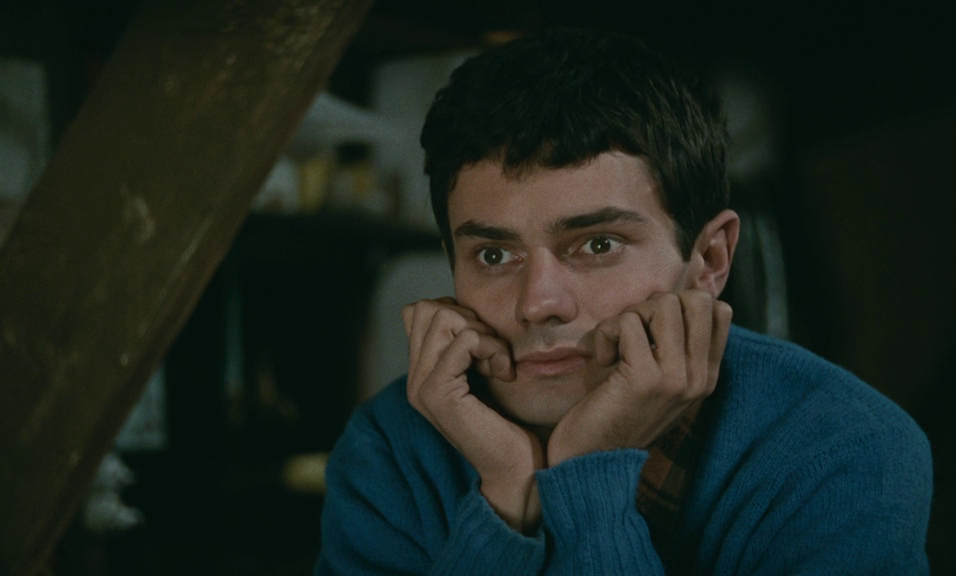

Response to Peary’s Review: While Lancaster “at first… refuses to acknowledge that civil war is taking place around him” — even “continuing his plans for a vacation with his wife (Rina Morelli), his dashing nephew (Alain Delon), and his seven children”: — very quickly “the face of Italy changes too drastically for him to ignore,” given that “the noble aristocracy of the past is being phased out” and “replaced by” not only “greedy military and political opportunists who switch loyalties at the drop of a hat” but by “shrewd and vulgar young people who will not carry on the dignified tradition.” Peary points out that “it’s unclear what Lancaster’s attitude toward” the “breathtaking” “Cardinale is — although he appears to approve of her and Delon because they at least have style.” He adds that the “picture has excellent acting, surprising wit, and glorious sets, costumes, and scenery,” as well as a “lush score” by Nino Rota. Peary’s assessment is fair, yet I struggled to find much connection with the storyline, which seems conflicted in its views on revolution. While it’s clear that social change is needed, we’re meant to (and do) relate to Lancaster’s central character (the “leopard”) — a man who represents everything noble and patient about a landed gentry which will nonetheless soon be overrun by a much more complicated national reality. I haven’t much more to say about this film, other than that it’s widely lauded and considered must-see for its visuals alone, which are indeed impressive — but I’m not really sure why American audiences in particular would feel drawn to this tale. Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments: Must See? (Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |