Woodstock (1970)

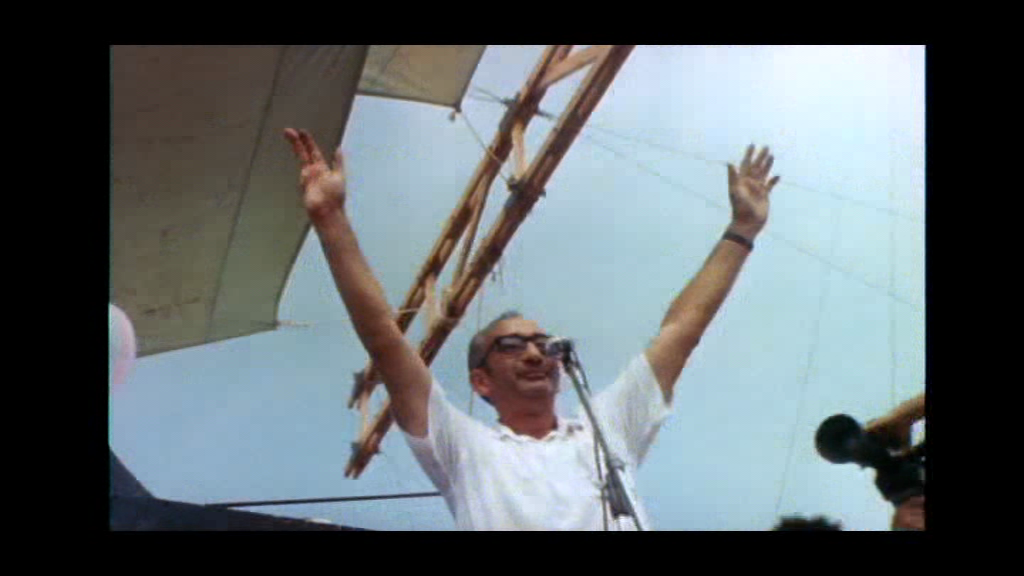

“I’m very happy to say we think the people of this country should be proud of these kids, notwithstanding the way they dress or the way they wear their hair — that’s their own personal business.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

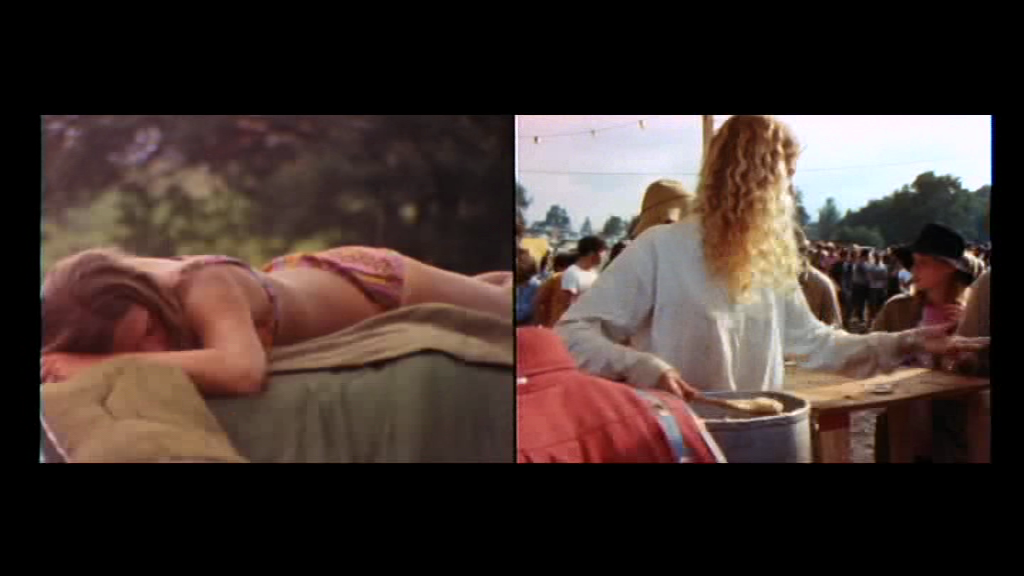

Response to Peary’s Review: There is much to enjoy about this engaging, smartly crafted documentary — but perhaps most impressive is how thoroughly the filmmakers provide as many perspectives on the event as possible. We hear from disgruntled neighbors, but also surprisingly generous and kind locals, such as those who stepped up to help feed the hungry crowds, or the cheery Port-a-San janitor who states he is “glad to do [his work] for these kids”. We see plenty of “turned on” participants having the time of their lives — but also listen to one distressed young woman desperate to escape the crowds. We hear a tireless worker sharing a hilariously rambling anecdote about trippers (“You wouldn’t believe some of the kids that come in here. They’re really spaced out. Last night, this cat, this cat comes in and says, ‘If anger is red and envy is green, what color is jealousy?’ And I mean, he’s really spaced out! And you just don’t go fucking people’s heads up when they’re spaced out! So I said, uh, “Black, right? Because jealousy is poison.'”) — but she then admits to feeling concern about her sister:

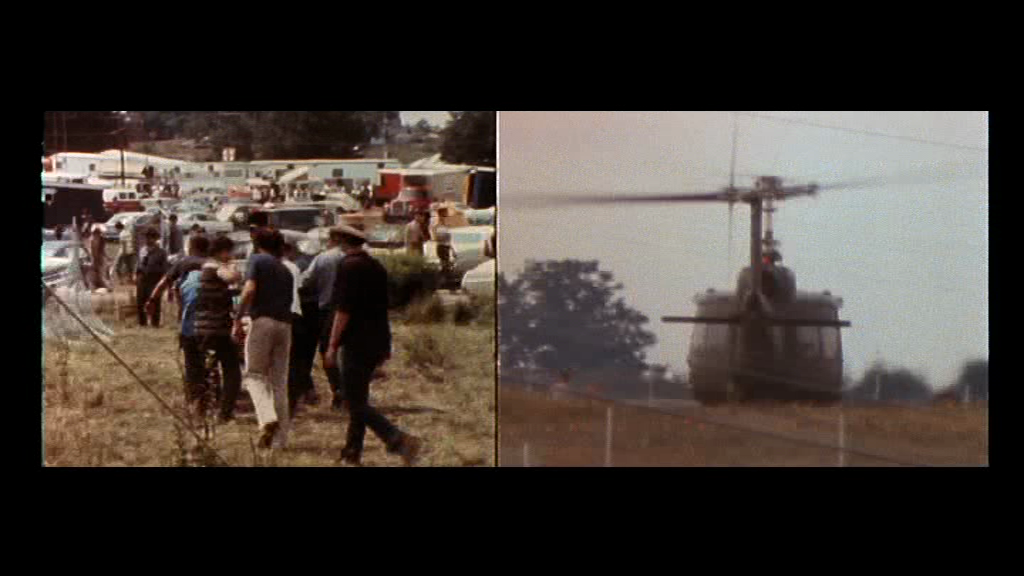

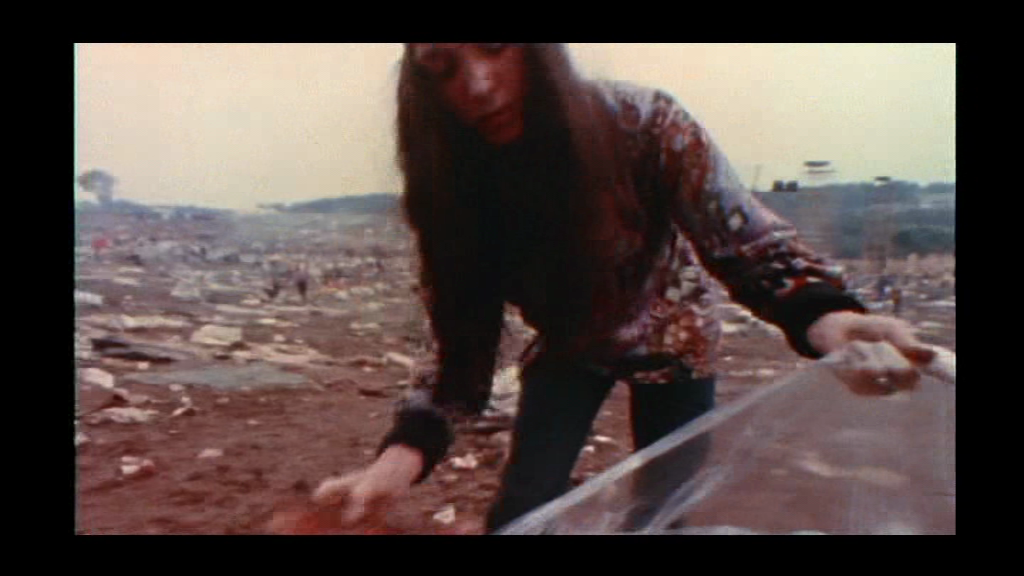

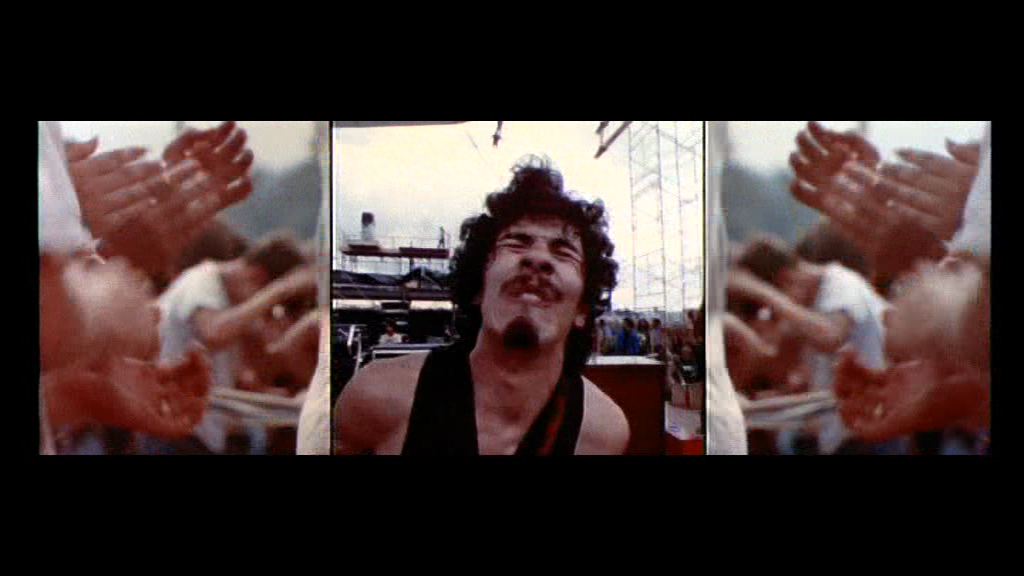

Speaking of home, we see kids lining up to make calls at a crowded telephone booth; sleeping like sardines on top of cars; skinny-dipping; caring for young children. We also see the tremendous amount of trash left behind after the concert (a detail most documentaries would shy away from); I was reminded of Frederick Wiseman’s films, which cover all facets — both important and seemingly insignificant — of what it takes to make an event or place run smoothly. One thing that distinguishes Wadleigh’s film from Wiseman’s, however, is his innovative use of split-screen imagery to show diverse perspectives on either a single moment or different points in time. The juxtaposition of concerned middle-aged neighbors with a shot of teens skinny-dipping is deliberately provocative, while other combinations simply help to convey the vastness of the event. Split-screen and super-imposition is especially extensive during musical sequences — to powerful effect, given that we can see both performers and viewers at once. IMDb notes that this stylistic choice was driven by necessity:

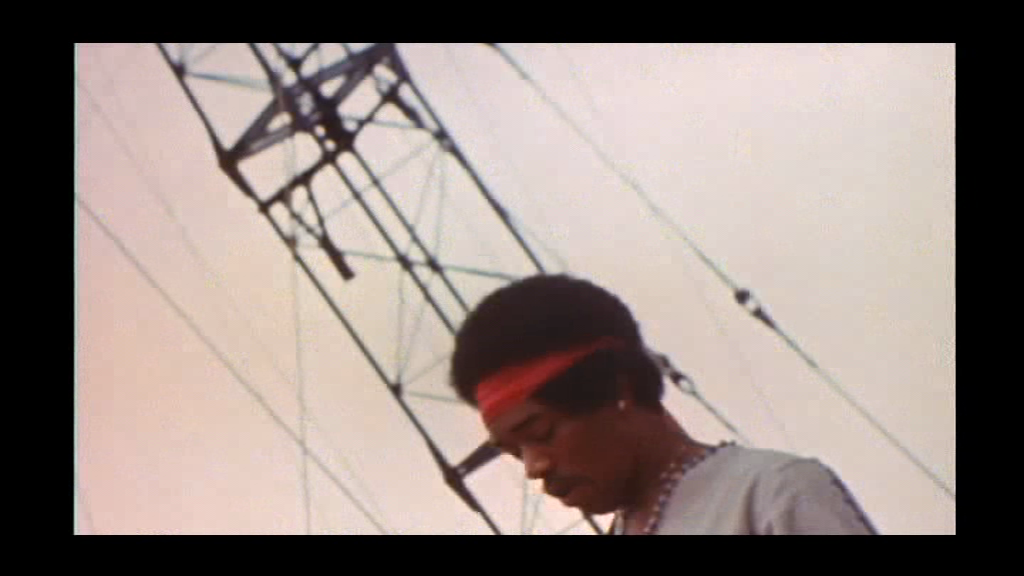

Interestingly, the musical performances ALMOST seem secondary to the ethnographic footage — though there are plenty of powerful songs, most notably Jimi Hendrix’s legendary riff on “Star Spangled Banner”. Interested viewers can read much, much more about this event — and the musical line-up — in numerous books or websites. Click here for a minute-by-minute overview of who performed when. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

Links: |

3 thoughts on “Woodstock (1970)”

A once-must (at least), for its place in both cinema and American history…and I’m rather in agreement with the assessment.

I don’t think I could sit through this again – but that has just about everything to do with me, and nothing to do with the considerable merits of the film. I saw it on release – was, no doubt, stoned. I then saw it again at least twice, and one of those viewings was the director’s cut. So I think I’m saturated.

[I also referenced Woodstock in one of my plays – ‘My Night with Rock Hudson’ – by giving a character a monologue about how she met her first serious heartthrob there.]

One reason another viewing would be tough for me is that I was never a big fan of a number of the groups. Not that I didn’t like hard rock – I just didn’t lean toward a number of these particular bands (~and, of course, Woodstock wasn’t only hard rock; nevertheless…).

That said…as a document of the time, the film is invaluable. And quite a charming relief compared with what happened with The Rolling Stones in ‘Gimme Shelter’ (from the same period). The two films together probably represent what America tends to be up against on a loop: the progressive vs. the anarchic.

It should be noted that ‘Woodstock’ exists in several versions (from what I hear, of varying sound quality), including extras of performances not included in a particular cut. Maybe one day there will be a massive re-edit available, and audiences will then be able to witness more of ‘the entire experience’. But…as a film, I don’t think you can go all that wrong with the original 3-hour version.

This was actually my first time sitting through the entire film of Woodstock, and it was an especially melancholy experience given the recent shooting in Las Vegas. I kept thinking: “There’s no way — simply no way — an event like this could be pulled off these days without tragedy of some kind.” I know Woodstock is overly romanticized, and Gimme Shelter shows the dark side of the same era — but I was sure happy to let myself drift into the communal comfort of this one.

It also made me think quite a bit about my childhood; my parents were hippies-of-a-sort, though they never took drugs. They were on a spiritual high, relying heavily on the support of the “brothers and sisters” in the spiritual group they belonged to, and much of what I see here reflects that overall approach to life.

And finally — yes, it’s curious that the musical performances here don’t stand out as much as one would think, though many are enjoyable.

I saw this for the first time when I was 14 on a VHS tape from the library. It was the original theatrical cut as David described. I watched it over and over—not unlike Charlton Heston’s character at the beginning of The Omega Man mimicking dialogue from it. I taped a number of the performances of that VHS so I could listen to it on my Walkman while mowing lawns on the weekend. My dad picked up a commemorative 20th anniversary Life magazine of the concert for me a few years prior on a sick day because he knew I was fascinated with that era as a kid.

I still think that this remains the greatest concert documentary ever made. Most concert movies tend to get quite dull quite quickly, in part because the performances don’t live up to the hype and there is usually no reprieve. In this case, it didn’t hurt that the event itself transcended the typical concert experience and provided so much raw material from so many different places to draw upon. It also didn’t hurt that so many of the concert goers’ anecdotes caught on film were thoroughly entertaining, touching and charming. I particularly enjoyed the use of split screen photography. Was it excessive at times? Perhaps, but it added a kind of vibrant quality, particularly during the performances. It was wonderfully edited: it doesn’t feel like a 3-hour movie.

There were some bands that were big winners at Woodstock. Santana served up a polyrhythmic masterpiece in Soul Sacrifice. Crosby, Stills and Nash had only two acoustic guitars and three voices, but sounded delightful on Suite: Judy Blue Eyes. The Who played like they had nothing to lose and ripped apart Eddie Cochran’s Summertime Blues. And there were more subdued but endearing performances as well. Arlo Guthrie and John Sebastian provided dry, laid back wit. And then there was the lovely voice of Joan Baez and the warm baritone of Richie Havens.

This truly was a singular event in how peaceful it really was. They initially charged people for admission, and then gave up because the attendance was too great. But the impact of that decision rippled into later shows. We all know about the Stones’ disastrous free Altamont show that December featured in Gimme Shelter. Watch the documentary to the Isle of Wight festival out of the UK from 1970 to see not-so-peaceful requests from loads of audience members as they insisted that the music be free, much to the shock of performers there like Joni Mitchell. Woodstock is still a marvel how it was all pulled off, and Michael Wadleigh crafted such a joyous and triumphant portrait of it.