“The only thing you’ve got in this world is what you can sell.”

|

Synopsis:

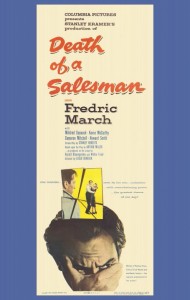

Aging salesman Willy Loman (Fredric March) pins all his hopes on his eldest son, Biff (Kevin McCarthy).

|

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Arthur Miller Films

- Father and Child

- Flashback Films

- Fredric March Films

- Kevin McCarthy Films

- Mid-Life Crisis

- Mildred Dunnock Films

- Play Adaptations

- Salesmen

Review:

Arthur Miller’s Pulitzer-prize-winning 1949 play has been produced on stage and for television many times (most notably with Dustin Hoffman in 1985), but only once for the big screen. Although the powerful material itself almost defies negative treatment, this early cinematic version by director Laszlo Benedek remains successful on its own merits. Benedek makes effective use of sparse sets and dramatic lighting to showcase Loman’s delusional despair, and directs a powerhouse team of actors (most of whom were part of the original Broadway cast; March is a notable exception). Especially poignant is Kevin McCarthy as Biff Loman; he perfectly captures both the teenage Biff’s naive idolatry of his father (in Willy’s flashbacks), and his adult resignation.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Fredric March as the delusional, aging salesman

- Kevin McCarthy as “Biff” Loman

- Mildred Dunnock as Willy’s long-suffering wife

Must See?

Yes. This first and only cinematic version of Arthur Miller’s acclaimed play deserves wider viewing.

Categories

- Noteworthy Performance(s)

- Oscar Winner or Nominee

Links:

|

One thought on “Death of a Salesman (1951)”

First viewing. A must.

It’s simply amazing that I have never come across this version on television. Since that was the case, I made the assumption that it is inferior. Wrong! As noted, the material is practically foolproof – well, as long as there’s a reasonably good cast. I’ve seen a few stage productions and three made for tv; whereas the other three leads have always been fine, I have to conclude that Frederic March as Willy Loman is what primarily makes this version a must (aside from the fact that it’s one of our best American plays).

Though other good actors have brought out Loman’s salient characteristics, March exudes a unique combination of befuddlement, vulnerability and panic – all wrapped in misplaced pride (i.e., why does Loman refuse his friend’s offer of a job when he needs another one so badly?). Though it’s hard to fight the feeling that Loman is ultimately pathetic – mainly since, in spite of all of his experience with the world, he’s hopelessly naive about how things work – I felt a kind of sadness for March that I hadn’t felt as strongly for Loman before.

The overall spirit of the play is very much maintained, even when the screenplay minimally departs from the original text. The theatrical mixture of memory/fantasy/reality is intact and works well. (It can be very tricky to adapt such character-driven, somewhat delicate stage plays; note, for example, the less successful film versions of ‘The Glass Menagerie’ and ‘The Member of the Wedding’.)