|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Asian-Americans

- Child Abuse

- Cross-Cultural Romance

- Donald Crisp Films

- D.W. Griffith Films

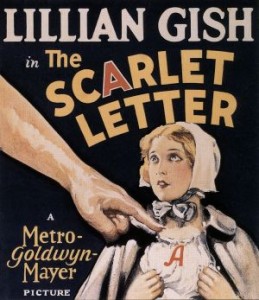

- Lillian Gish Films

- Racism and Race Relations

- Silent Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

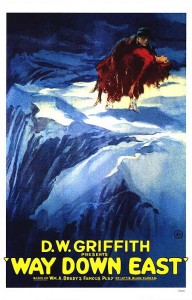

Peary refers to this “D.W. Griffith classic” — an unflinching early look at child abuse and racial prejudice — as “perhaps the cinema’s first outright tragedy”, yet points out that the use of various tints and the strategic employment of a “special soft-focus lens” gives the film “an almost poetic feel that tempers the harshness of the story”. He notes that the “overly sentimental” storyline (based on a short story by Thomas Burke) “surely appealed to Griffith because it again let him lash out at the evil city, again deal with miscegenation and suicide, and again — and this is the disturbing element — sacrifice an innocent girl to our cruel, immoral world.” Indeed, the three central characters are so elemental in their attributes — “snarling Crisp”, “stoical Barthelmess”, and timid Gish — that the wafer-thin story (not really suitable for a feature length film) comes across as more of a fable or a fairy tale than any kind of realistic narrative. This is especially true given that the age and developmental maturity of Gish’s character (Lucy) is left so vague: the 26-year-old Gish* could literally be either 10 or 15 or 20; she’s so petite and huddled over from fear at all times that we can’t really tell — and when Barthelmess hands her a doll to play with (!), we get seriously confused. (In the original short story, the character was 12 — which I suppose lends some credence to this scene.)

The film’s terribly antiquated, casually racist subtitle will likely turn many modern film fanatics off; but once they make tentative peace with both this and the (then standard) casting of white men in both central Asian roles, they’ll likely be pleasantly surprised to find that Griffith — the infamous director of America’s most egregiously racist classic film, Birth of a Nation (1915) — seems to at least be trying to portray the film’s Chinese-American protagonist (Cheng) in a reasonably respectful light. Indeed, it’s gratifying to know that Griffith “considered the main theme of his film to be that Americans wrongly consider themselves superior to foreigners, including the Chinese, who have a noble, peace-loving philosophy”. Cheng is shown at the beginning of the film to be a noble-minded Buddhist missionary hoping to convert European heathens to more peaceful ways — and thus his quick descent into opium addiction after arriving on the sordid shores of London is given a bit of context and justification, rather than simply perpetuating the trope of drug-addled Asians. (Actually, as I think about it, this piece of the narrative could easily have been expanded upon: I’d love to have seen more of Cheng’s travails upon arrival in London.)

At any rate, Cheng’s poetically romantic yearnings towards Lucy could be (and are) explained away as merely a platonic desire to love and assist that which is most pure and good in the world — though, again, it would have been much more fulfilling to see this most unusual cinematic couple actually moving towards something “real” together. This would have required a more substantial storyline in general, but at least would have given a shred of credence to the fantastical poster (shown above). In terms of the lead performances, Peary accurately argues that “Crisp overacts”, “Barthelmess under-acts (as if he believed one change of expression would let us know that he isn’t really Oriental after all)” — but Gish “acts up an exciting storm”. He notes that “from her timid talking, stooped, crooked posture, and terrified eyes, Gish immediately gets us to understand that her beatings are a daily thing for her”, and she is “totally convincing” in the role. Her character’s ability to “smile only if she lifts the sides of her mouth her fingers” was apparently thought up by Gish herself, and remains one of the film’s most indelible (recurring) images.

* TCM’s article lists Gish as 23-years-old when the film was made, but this doesn’t make mathematical sense, given that IMDb cites 1893 as her birth year.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Lillian Gish as Lucy, “the waif”

- A (relatively) bold exploration of both child abuse and cross-cultural companionship

- Billy Bitzer’s cinematography

Must See?

Yes; despite being “a bit disappointing”, it’s nonetheless considered a silent classic, and “is essential to any study of Griffith”. Selected to the National Film Registry, Library of Congress, in 1996. Available for free viewing at www.archive.org.

Categories

- Genuine Classic

- Historically Relevant

- Important Director

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|