Passage to India, A (1984)

“India forces one to come face to face with oneself.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

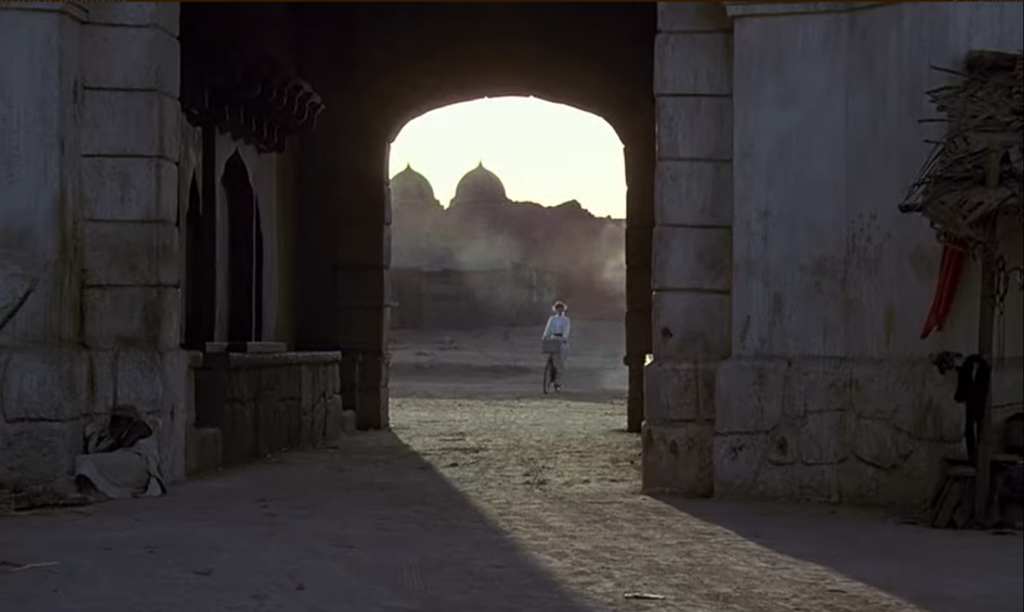

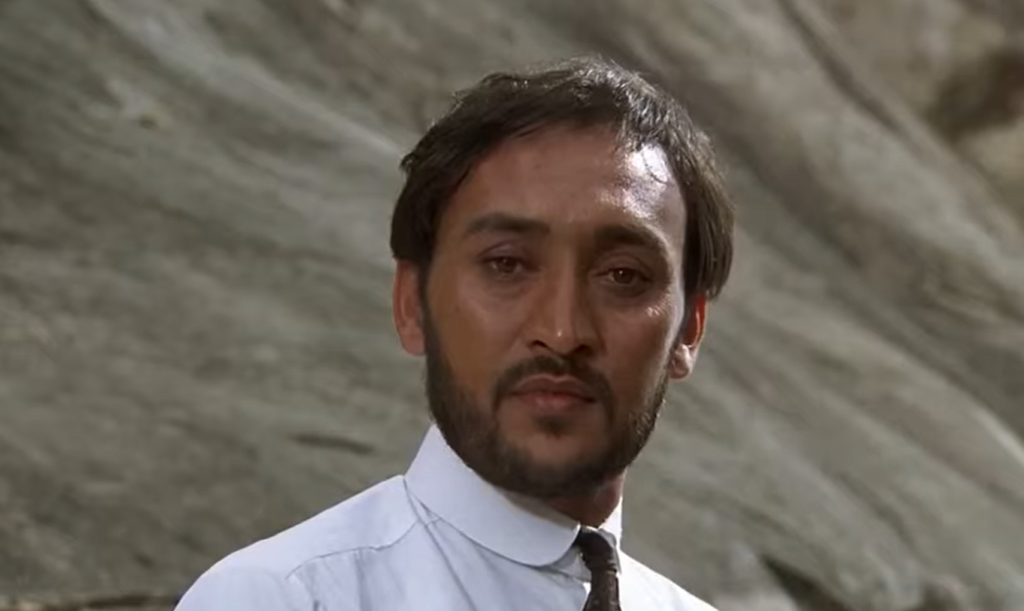

Response to Peary’s Review: I’m ultimately more taken with this adaptation than Peary seems to be. Of course the issue of “what happened in the caves” is of paramount importance — and was famously never revealed by Forster himself — but is meant to be shrouded in mystery, as it is here. (I disagree with Peary’s suggestion that the film indicates Aziz “did attempt something” and “might have been guilty.”) What is clear, however, is that Adela’s ambivalence over whether or not to marry Havers — combined with the sensory overwhelm of being in a hot new country with so many sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and customs to become used to — combine to put her into a decidedly hallucinatory and unwell state. As DVD Savant writes in his review, “In one of the best-edited scenes, Lean communicates Adela’s sexual fear in a confrontation with erotic sculptures and a horde of very non-cute monkeys. She’s never even in the same frame with a monkey, yet Lean makes us feel their threat. Monkeys show up at several key moments in the movie, and seem to represent the savagery and sexual chaos that the British fear in the Indian culture.” To that end, Lean does a powerful job representing the very-real tensions between colonial Britons and fed up Indians, who are rightfully ready for change and increasingly intolerant of Britain’s patronizing attitudes and actions. Dr. Aziz (Banerjee) personifies this tension, with his attitude shifting over the course of the film as he gradually realizes that his own well-being — and that of his nation — will depend on extrication from his desire to “present well” to the British. Fox’s role (though minor) is equally pivotal in the movement towards respectful equality between Indians and the British. While Peary writes that “it’s hard to tell if Lean is trying to impress us with the glorious scenery or the cinematography itself”, this comment doesn’t make much sense — he does impress us, but I’m not sure how or why this is problematic. India’s landscape is indeed gorgeous and awe-inspiring, and Ernest Day’s cinematography is stellar. Meanwhile, the performances across the board — particularly by Davis, Ashcroft, and Banerjee: — are outstanding, with just one exception: Lean’s selection of Alec Guinness to play a minor role as a Hindu-Brahmin professor feels decidedly antiquated and inappropriate. (They apparently didn’t get along well on set.) However, Guinness is on screen for such little time that it doesn’t much impact the overall movie. This remains a powerful, finely crafted epic by a master director, and is well worth a one-time visit. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

One thought on “Passage to India, A (1984)”

A once-must, for its place in cinema history, Lean’s direction and the performances (esp. Davis).

Overall, my enthusiasm for Lean’s work rests more with a number of his earlier films (‘In Which We Serve’ through ‘Oliver Twist’, not including ‘Blithe Spirit’). Following that period (with the exception of ‘Hobson’s Choice’), I feel a strain in Lean’s work – like he’s trying too hard. (The one I remember least is ‘Dr. Zhivago’; it’s been too long and I’ll need to revisit it.)

‘A Passage to India’, in a number of ways, stands out as a fine return to form and a fitting conclusion to a career. I esp. like its sense of emotional mystery. I’ve always felt it appropriate that the story avoids a depiction of rape – since it’s clear (to me, anyway) that it never happened. It’s an effective portrait of a neurosis brought on by a repression that results in general inner-turmoil.