Night of the Hunter, The (1955)

“There’s too many of them. I can’t kill the world.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres:

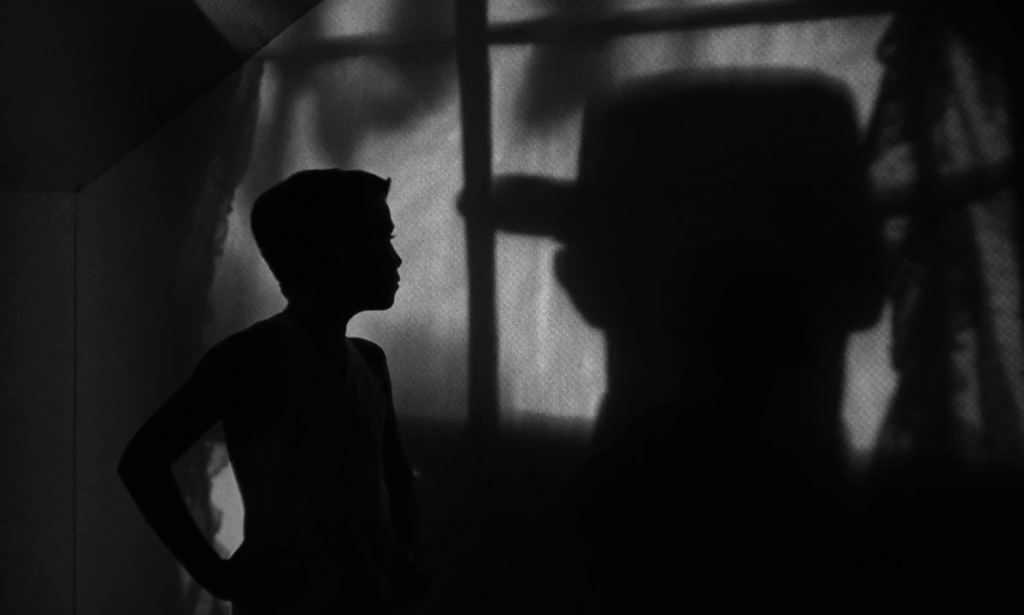

Response to Peary’s Review: Once Chapin and the doll-like Bruce (that forehead!) go on the lam from the predatory Mitchum, Peary accurately likens them to “Hansel and Gretel, traveling through the woods, heading downstream — only they find a sweet old lady” (Gish) rather than a witch. In his more extensive review of the film for his Cult Movies 3 book, Peary admits that he gets “all choked up about halfway through [the film], anticipating Rachel [Gish] coming to the aid of the two desperate children”. He notes “how brave, unselfish, and caring she is”, as the only adult in the film who “recognizes their need for help, and the only one who has the inner strength and the faith to help them”. To that end, “strong-willed Gish and strong-bodied Mitchum are great opponents” — what inspired casting on both counts! Other performances in the film — from Winters as Mitchum’s doomed new bride, to Evelyn Varden as a nosy, self-righteous neighbor named Icey Spoon (!) — are fine as well; but what’s most striking about the film is Laughton’s utterly “audacious visual style”, turning nearly every frame of the picture into a memorable tableaux (see stills below). As Peary notes, Laughton “borrowed from D.W. Griffith (Gish’s most famous director) and German Expressionists” to create a highly stylized alter-universe which “immediately takes us out of reality”. The film’s enormously creative opening scene, for instance, has “harsh music… replaced by the sweet singing of children and the heads of Rachel and her five young wards appear[ing] in the sky, amidst the stars”, providing just a hint of what’s to come — no ordinary 1950s Hollywood melodrama, this! (And speaking of the opening shot, it’s intriguing to wonder whether the entire film might be, as Peary suggests, “the nightmare John [Chapin] has… after hearing Rachel’s fretful words”. Hmmm…) Regardless, we’re taken on a humdinger of a ride — one we can’t ever pull our eyes away from, no matter how frightening the story becomes. This is thanks in large part to the consistently striking beauty of Laughton’s visuals, but also due to how Laughton deftly infuses this most tragic of tales (about murder, theft, deceit, and child abuse!) with plenty of alleviating dark humor. He does this by turning Mitchum’s psychopathic preacher into a “classic deceitful fairy-tale villain”, one who supplies unexpected “slapstick humor” and thus provides the film with its “necessary moments of relief”. Yet for all his cartoonish qualities, Mitchum remains a serious presence to be reckoned with throughout — a truly crazy “messenger of God” who will do anything, absolutely anything, to get that $10,000. Watch and be afraid. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) Links: |

One thought on “Night of the Hunter, The (1955)”

Lord have mercy, a must! 😉

So…the great actor Charles Laughton directed only one film! Well…well!…if your legacy is going to be just one…it better be as good as this!

And, to think…it was a box office flop. Ye gods! What is wrong with people?! Thankfully, today it is held in quite high regard and its position as a cult film and great movie-making is firmly in place.

I can’t even begin to go on about how brilliant this film is. The whole thing is designed as a frickin’ nightmare – mostly in shadows and angles, mixed with very disorienting reality.

What’s most unusual – and what sends this film over – is the perfect marriage of director and director of photography. Although he did not direct for film prior, Laughton had directed for the stage (admirably, one would think). And as for Stanley Cortez…it’s not as if the guy has a long list of first-rate classics on his resume. Yes, he did high-profile films such as ‘The Magnificent Ambersons’, ‘Since You Went Away’, and ‘The Three Faces of Eve’…but he also went low-budget indie with two Samuel Fuller films…and…how is this possible?, worked on ‘The Ghost in the Invisible Bikini’, ‘The Navy vs. The Night Monsters‘ and ‘They Saved Hitler’s Brain’. I mean…huh?! (He apparently did uncredited work on ‘Chinatown‘.) Cortez’s work on this film – in close collaboration with Laughton re: style and lighting – is just about one piece of stand-on-its-own artwork after another. Just stunning. (A particular fave comes when the protagonist children are sleeping in a barn; we are given a view of the sky and watch a crescent moon as it rises with the passing of time, from lower left to front center to upper right.)

Writer James Agee (who died at age 45, the year this film was released) basically brought this and ‘The African Queen’ to the big screen as adaptations. His work here in particular is sharp and economic – reportedly, Laughton was quite astute in getting Agee to cut-cut-cut; most scenes are brief and to the point. I’ve not read the (apparently out-of-print) novel – based on a real serial killer – but, from some accounts, the film is seen as an improvement in some significant ways. It appropriately plays like a bat out of hell, and is also sprinkled with moments of hilarity.

A number of those moments come from the mouth of (the amazing) Varden when she talks directly or indirectly about sex:

– “When you’ve been married to a man 40 years, you know all that don’t amount to a hill of beans. I’ve been married to my Walt that long and, I swear, in all that time, I just lie there thinkin’ about my canning.”

– “A husband’s one piece of store goods you never know ’til you get it home and take the paper off.”

But the humor comes from various other sources as well, perhaps none as surprising as when Winters is looking through Mitchum’s coat pockets and finds his switchblade:

– (to herself) “…Men.”

What’s most fascinating about Mitchum’s pitch-perfect performance is that his character’s twisted mind is the product of a warped view of religion. He believes he kills *for* the Lord. (This resonates strongly when one thinks about the groups of people in countless countries who kill in the name of ‘God’.) When Graves asks Mitchum in jail exactly what religion it is that he preaches, the response is telling: “The religion the Almighty and me worked out betwixt us.” – yet it is a response that simultaneously says absolutely nothing since it is cloaked in secrecy. Note later in the film as well: at one point, Mitchum stands not far from Gish’s house singing “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms”; from the house, Gish joins in – only her lyrics include the name of Jesus (a name absent when Mitchum sings).

~and is it just me?…or, early on, when we see Mitchum watching a stripper and he reaches for his switchblade…are we to think that killing does indeed serve the exact same purpose for him as sex? This is one messed-up dude.

Gish herself plays an intriguing woman, made of tough love (in tough times) yet firmly rooted in faith and compassion. She knows human nature and, even if you ‘get up pretty early in the morning’, you really can’t fool her. She also doesn’t seem to have all that high an opinion of herself – in the sense that her humility shines through: “I’m good for somethin’ in this old world, and I know it, too.”

It doesn’t go unnoticed that Winters also gives one of her strongest performances here – even tho she’s playing something of a dolt (~something Graves clues us into early on; it’s no surprise later when Winters becomes something of a religious zealot when there is so little going on in her ‘attic’; but note the howl of repressed passion when Mitchum withholds sex on their wedding night).

My understanding is that Laughton was not thrilled with the idea of working with children and left some of the ‘kid stuff’ to Mitchum. Whatever the truth is there, the children hold their own rather well. Chapin and Bruce do not have typical kid parts to play – a lot rides on them – and they’re both memorable.

It really is a shame that Laughton allowed initial audience response to have influence over him. Still, we at least have this one film – and it’s one that holds up quite well to repeated viewings, offering more with each visit.