|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Actors and Actresses

- Clowns

- French Films

- Love Triangle

- Romance

- Star-Crossed Lovers

Response to Peary’s Review:

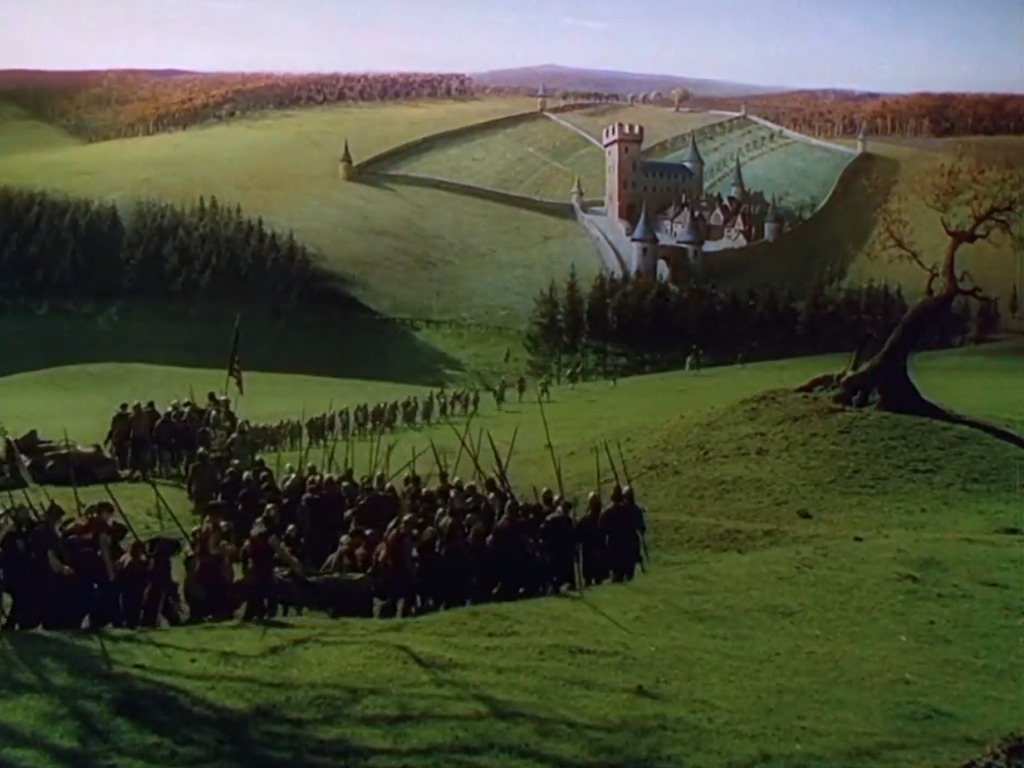

Peary is among the many critics and fans who consider this “fifth collaboration between director Marcel Carné and screenwriter Jacques Prévert” to be “one of the glories of the cinema, the romantic’s delight, the sophisticate’s cult favorite.” He notes that when it “opened in Paris in March 1945,” it was “quickly hailed as France’s Gone With the Wind: an epic, a re-creation of a nineteenth-century period (that of Louis Philippe) and setting (the Boulevard of Crime)”:

… and “a romance about a woman… who is coveted by all men who see her.”

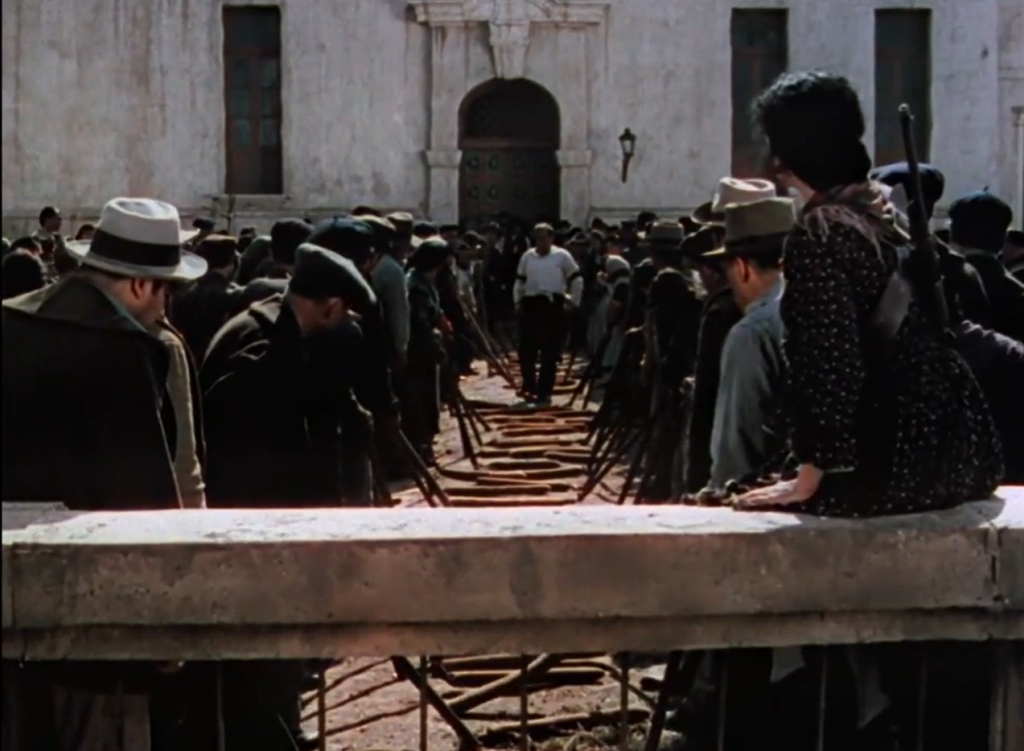

However, he points out that “the real reason the French held it so dear was that it was one of the cornerstone films of le cinéma d’évasion” — i.e., “the French film industry’s brave response to the German occupation.” Indeed, he asserts, “It’s amazing that this affront to the Nazis, which celebrates a free France, could be made under the noses of the occupation authorities” — and while I don’t quite see how this film epitomizes a “free France”, I’ll agree it’s remarkable that Carne and his team managed to get it made at all under the circumstances, including “secret filming [that] took place over two years in garages and alleys, during which time time members of the French resistance were able to hide from the Gestapo because they were among the 1800 extras employed.”

Peary argues that this “film is a wonderful tribute to the people who have never been controlled by authority: lovers, mountebanks, rogues, criminals…, artists, the poor who crowd the inexpensive rafter seats, ‘gods’ (paradise) of the theaters, and, most of all, performers” — and he notes that it’s “a cry for a return to the past, for liberty, for solidarity between artists and their public, for solidarity among all French people.” I’m not sure I see all these themes playing out, but can appreciate how one might, especially at the time of the film’s release.

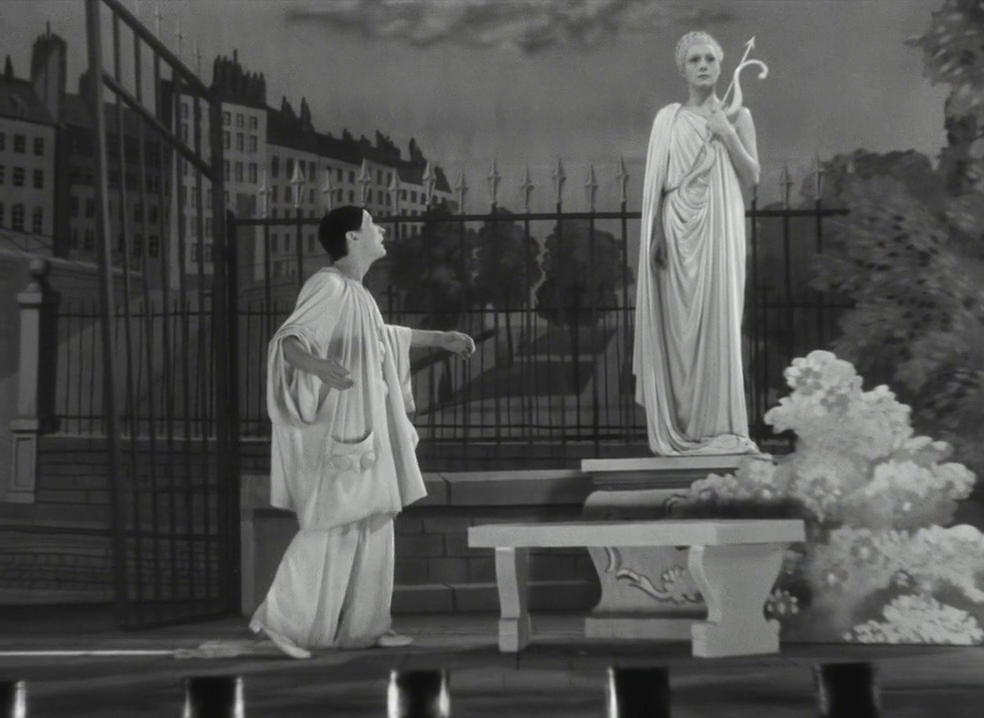

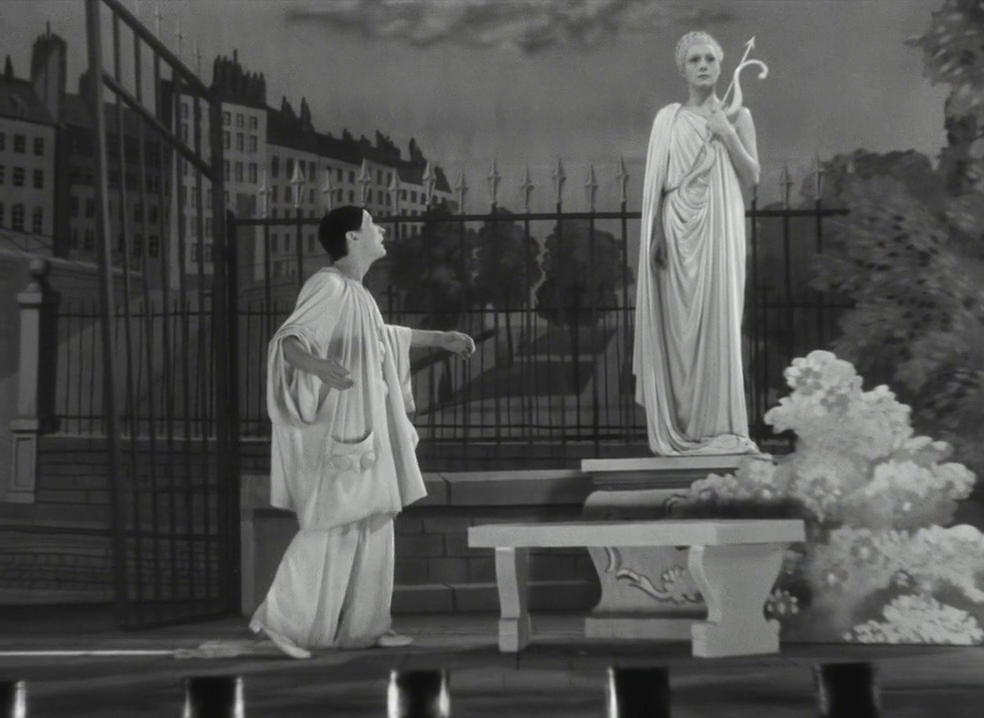

Meanwhile, Peary discusses the (fictional) role played by Arletty, in contrast to the three real-life people portrayed by Barrault (Jean-Gaspard Deburau), Brasseur (Frederick Lemaitre), and Herrand (Pierre-Francois Lacenaire). He notes that Arletty’s Garance is viewed by men “as an angel, a dream, a vision of beauty, [and] Venus,” and Peary himself sees her as “the symbol of Paris,” or even perhaps Paris itself: “beautiful, freedom-loving, full of memories, as proud of the gutter dwellers as of the elite, lover of every man, the betrayer of none,” “in whose presence hearts begin to flutter.”

Arletty was 47 at the time of the film’s release, and while she’s certainly alluring for une femme d’un certain âge, I find it fascinating that she’s so universally coveted by the four leading men in this movie — especially by Barrault (35 at the time), who has beautiful Casares (23 years old) waiting adoringly in the wings for him (though obviously, age and looks are beside the point when it comes to obsessive love).

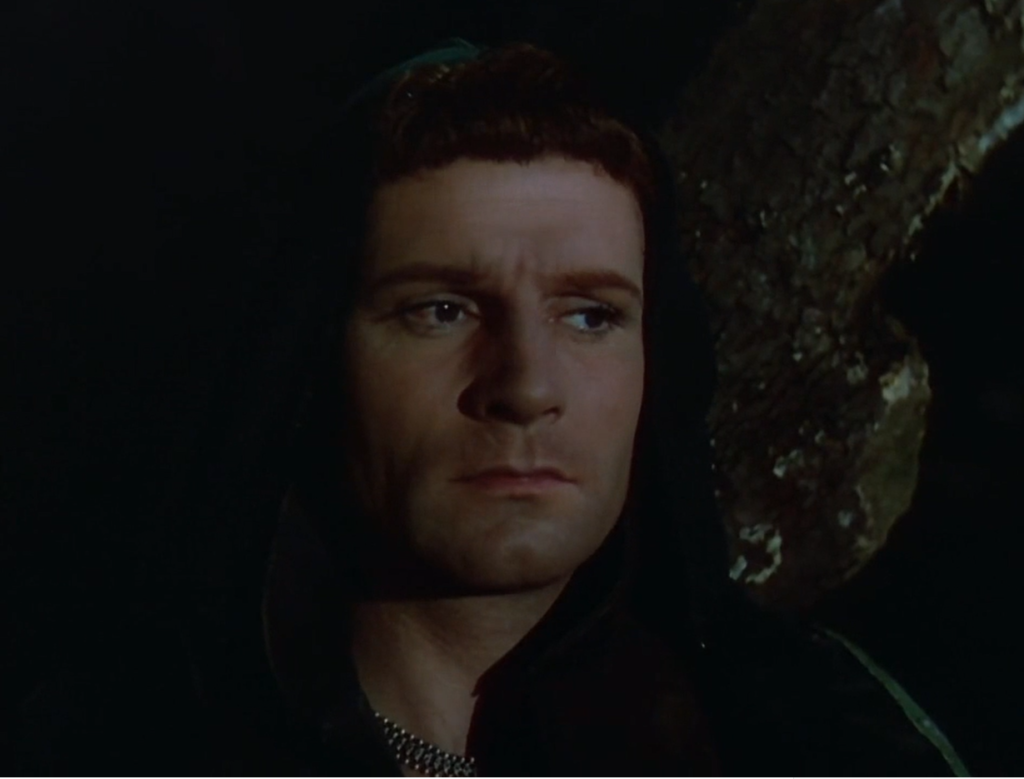

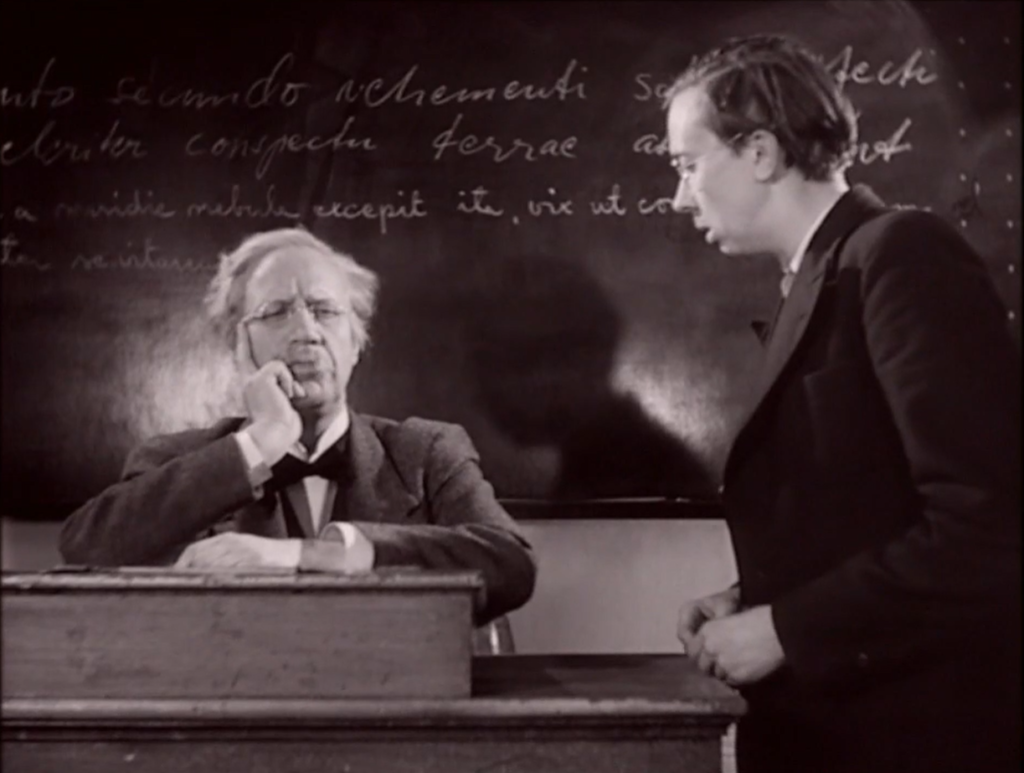

Peary goes on to write that the “picture’s acting is superb,” that “Barrault’s mime performances” are classics” (agreed):

… that “the visuals are opulent,” and “the elaborate sets are rich in detail and historically accurate.”

Peary describes this film in further detail in his Cult Movies 2 book, where he elaborates on its “stolen kisses” theme (i.e., “people desire only those they cannot have”), discusses the poetry of Prevert’s script, and notes that “lithographs and woodblock prints of the period were studied” to bring about the truly impressive sets.

This lengthy movie — actually divided into two separate films — isn’t a personal favorite, but I can understand its appeal, and upon my rewatch of the beautiful restoration I found myself thoroughly enchanted by Barrault (not just his miming, but his overall performance).

Children of Paradise most certainly remains a must-see classic at least once.

Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments:

- Jean-Louis Barrault as Baptiste

- Pierre Brasseur as Frédérick Lemaître

- Marc Fossard and Roger Hubert’s cinematography

- Magnificent sets and overall production design

- Mayo’s distinctive costumes

Must See?

Yes, as a foreign classic.

Categories

- Foreign Gem

- Genuine Classic

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|