Reflections on Must-See Films From 1963

Given that Peary lambastes 1963 in his Alternate Oscars as a cinematic year unworthy of any Best Picture contenders, I was curious to take a look at how many titles from this year struck a chord with me — and was pleasantly surprised to see that quite a few are worth mentioning. Out of 74 total titles, I voted 32 — or ~43% — as must-see; here are just a few. (We’re seeing a lot more color than in 1962, btw.)

- Numbers wise, only six of the 32 titles are in a language other than English: one in Japanese (Kurosawa’s High and Low), three in Italian (Fellini’s 8 1/2, Mario Monicelli’s The Organizer, and Vittorio de Sica’s Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow), and two in Spanish — including the powerful Spanish documentary To Die in Madrid.

- Several are British — including Peter Brook’s adaptation of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, made with an unusual amount of creative leeway and resulting in “an appropriately terrifying tale about leadership (or lack thereof) run amok.”

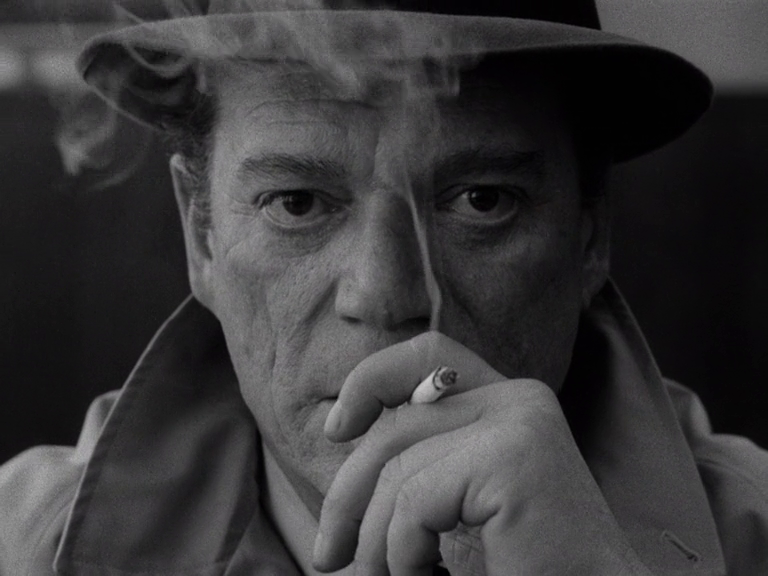

- I’m also a fan of Joseph Losey’s creepy The Servant — featuring shadowy cinematography by Douglas Slocombe and starring Dirk Bogarde as “a calculating and unflappable servant-for-hire who knows exactly the right moves to make at each moment as he pursues his self-serving, often inscrutable goals” while helping to care for an alcoholic financier (James Fox).

- British director Alexander Mackendrick’s little-seen A Boy Ten Feet Tall (a.k.a. Sammy Going South) tells the unusual story of a ten-year-old boy (Fergus McClelland) embarking on a trek across Africa to find his aunt, and encountering Edward G. Robinson’s grizzled jewel miner along the way. McClelland and Robinson are excellent together, and the cinematography by Erwin Hiller is often beautiful.

- Murder at the Gallop remains a delightful Agatha Christie adaptation featuring jowly Margaret Rutherford as “prim, spinsterish Miss Marple.” As I note in my review, “With her otherworldly facial grimaces and her indomitable lust for sleuthing (and snooping), Rutherford carries the film with ease.”

- From all of 1963’s titles, what stands out most is Hitchcock’s The Birds — one of his most unique and suspenseful thrillers, telling a metaphorically rich tale of a seaside town overtaken by gulls, crows, ravens, sparrows, and finches — for unknown reasons…

“Why are they doing this? Why are they doing this? They said when you got here the whole thing started. Who are you? What are you? Where did you come from? I think you’re the cause of all of this. I think you’re evil. EVIL!”

- The second James Bond film — From Russia With Love — is a worthy successor to Dr. No (1962), featuring a couple of memorable villains: blond Robert Shaw as a psychopathic British traitor, and Lotte Lenya as diabolical Rosa Klebb.

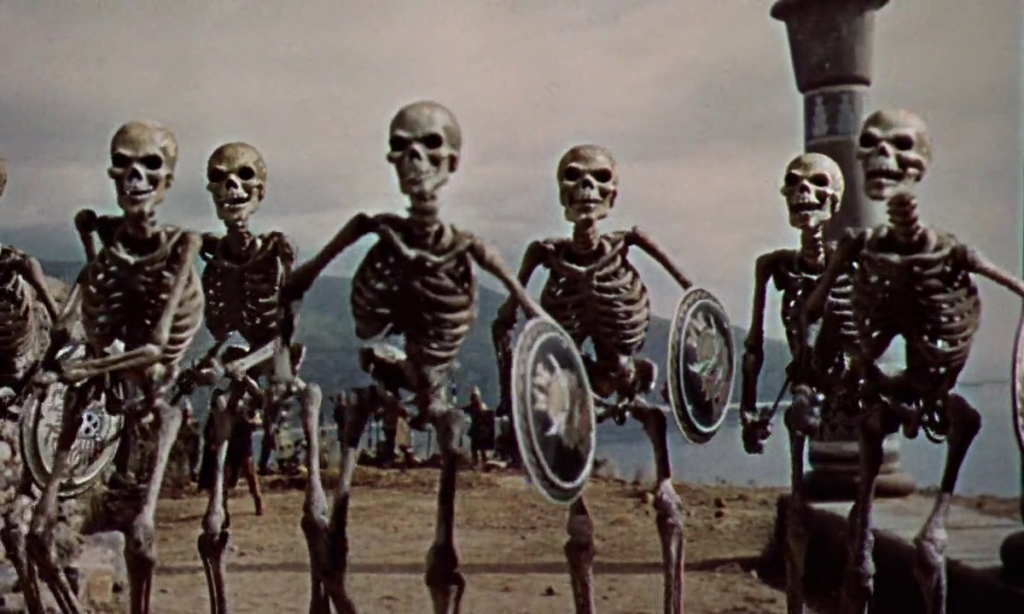

- Jason and the Argonauts showcases some of Ray Harryhausen’s most memorable stop-motion animation, including (of course) the sword fighting skeletons, but also the giant statue of Talos coming to life and gruesome harpies relentlessly plaguing blind Phineus.

- Martin Ritt’s Hud, a “film about alienation in all its forms,” is brutal viewing — worth watching for the powerful performances by co-stars Paul Newman and Patricia Neal, but not likely to engender much desire for a revisit.

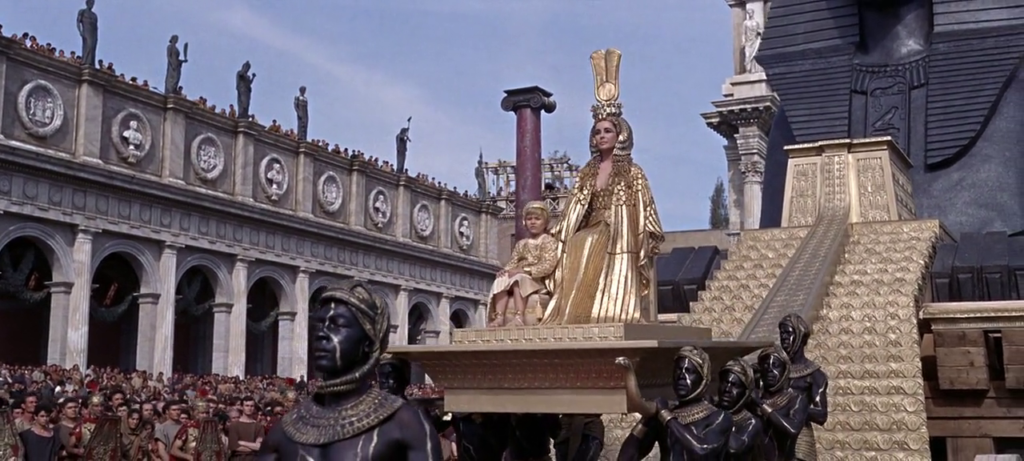

- Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s Cleopatra — notorious for its overblown budget and multi-year filming saga — is actually “a reasonably engaging (if over-long) saga of opulence, narcissism, treachery, and high drama among the elite ruling class,” with literally “no expense [being] spared to (re)create a vision of ancient Egypt and Rome fantastic enough to represent the delusional grandeur of such fabled rulers.” It nearly took down 20th Century Fox.

- Finally, Roger Corman’s low-budget sci-fi thriller X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes remains an enjoyable flick about the “inevitable downward spiral of a man [Ray Milland] who has… clearly become a ‘freak’ of nature, demonstrating that one “who can see ‘everything’ may have access to universal secrets best left untapped.”

“We are virtually blind — all of us.”

As I’m reflecting on all these titles, I’m seeing a definite theme of terror and unease mixed with revolution and resilience. Life was getting increasingly challenging, and cinema was showing this in a variety of forms.

I look forward to seeing where 1964 takes us!