|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Actors and Actresses

- Alcoholism and Drug Addiction

- Fassbinder Films

- German Films

- Has-Beens

Response to Peary’s Review:

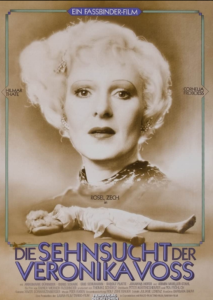

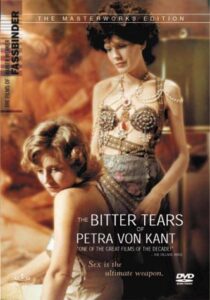

Peary seems less than enthusiastic in his review of this “rare uncomplicated Fassbinder picture”, the “last film in… Fassbinder’s postwar trilogy, following The Marriage of Maria Braun and Lola.” Loosely based on the career of UFA actress Sybille Schmitz, it tells an absorbing tale of addiction, dependence, and domination, with Thate’s everyman journalist finding himself unexpectedly lured into Zech’s troubled existence. Peary cites the film as “of interest mainly because of what Veronika Voss represents”: both “the once great, proud Germany that shrinks away in pain, guilt, and humiliation and the victims of the postwar social order.” In addition, he notes that “Fassbinder, who often identified with his heroines, probably related to Veronika Voss’s drug addiction since his own dependency was increasing at the time”, and conjectures that “perhaps Fassbinder sensed [that] his imminent demise… would be similar to Veronika Voss’s”.

I find the film much more enjoyable than the above analysis would indicate. While it’s certainly of interest on a number of historical and thematic levels, it also simply “works” as a compelling, finely acted character drama. Xaver Schwarzenberger’s rich black-and-white cinematography and Rolf Zehetbauer’s stark set designs (note the blindingly white quarters of Dr. Katz’s “office”) help to create an “other-worldly” post-WWII landscape, one which resonates effectively with Voss’s warped existence. Indeed, the film is a fascinating combination of standard melodrama (Fassbinder was heavily influenced by Douglas Sirk) and post-modern surrealism: in one of the movie’s strangest scenes, for instance, Zech openly propositions Thate in front of his girlfriend (Cornelia Froboess), who thus knows about his betrayal yet ends up assisting Thate in his attempt to uncover the truth behind Zech’s mysterious relationship with her doctor (Duringer). Film fanatics — whether fans of Fassbinder’s oeuvre or not — are sure to find this one worth a look.

Note: Parallels are often made between this and Billy Wilder’s masterful Sunset Boulevard, given that both Zech’s Veronika Voss and Gloria Swanson’s Norma Desmond are aging “has beens”, desperate for a resurgence of their failing careers, who lure an impressionable young man into their troubled lives. This is definitely the darker of the two.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Rosel Zech as Veronika Voss

- Hilmar Thate as Robert Krohn

- Cornelia Froboess as Henriette

- Annemarie Duringer as Dr. Katz

- Striking b&w cinematography

- Effectively stark sets

Must See?

Yes, as one of Fassbinder’s most compelling films.

Categories

- Foreign Gem

- Important Director

Links:

|