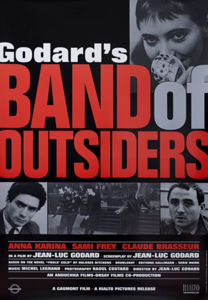

Band of Outsiders / Bande à Part (1964)

“Arthur said they’d wait for night to do the job, out of respect for second-rate thrillers.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

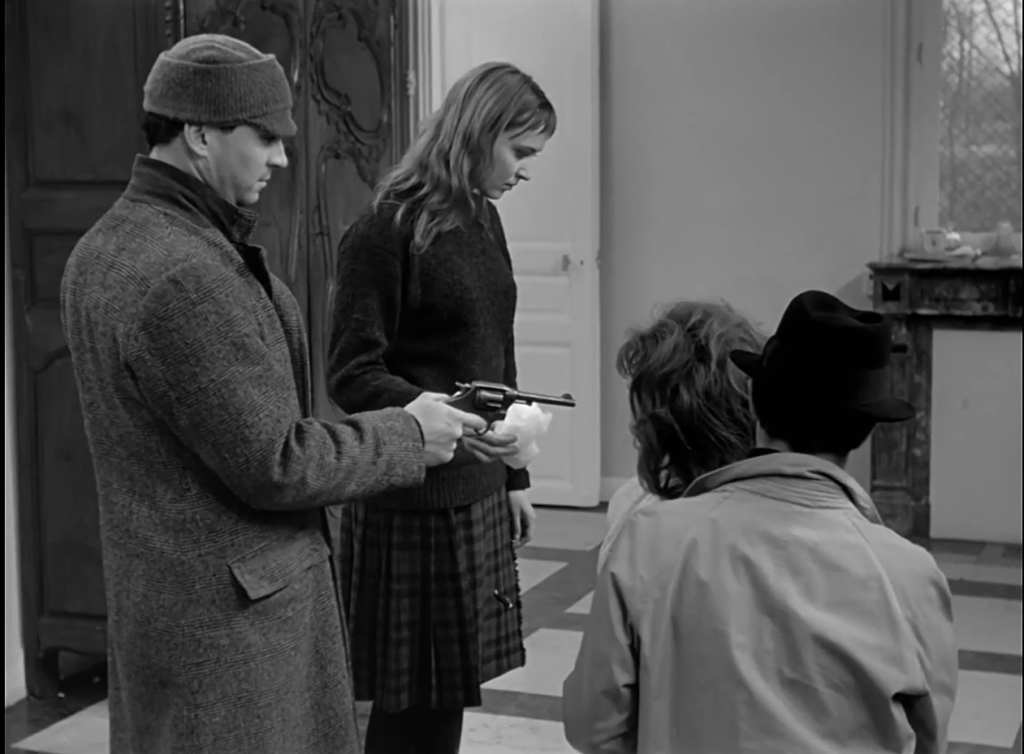

Response to Peary’s Review: Because “their mutual girlfriend [?!], Anna Karina, wants to fit in,” she “offers a real crime to them: they can steal her aunt’s money” — but “the three bumbling… amateurs… can’t distinguish between fiction and real life.” Peary notes that “when they put on their movie criminal guises, they think of themselves romantically, as do Sissy Spacek and Martin Sheen in Badlands [1973] when they commit equally unromantic crimes; but, as is the case with Spacek and Sheen, their guns shoot real bullets and people get hurt.” Peary points out that “the overlapping of reel life and ‘real life’… is disorienting because we have a hard time figuring out the logic of the characters’ actions” — however, while he argues this is “excitingly original,” I simply find it frustrating. We know far too little about these three uninteresting characters, other than that Karina’s Odile is for some reason hopelessly insecure (she wears primarily one expression — worried and uncertain — throughout the film): Sadly, this makes sense on a real-life level, given that according to TCM’s article, “At the time Karina was recovering from losing a child during her pregnancy followed by a suicide attempt… The relationship between Karina and Godard was also on shaky ground by this point in their marriage and they would soon go their separate ways after working together on Alphaville (1965).” However, it’s frustrating as a viewer watching this beautiful young woman (who has a dark side of her own) caving in time and again to her (occasionally abusive) male partners; they bullishly get their way, but at obvious and inevitable costs. And what, exactly, does Karina see romantically in Brasseur? I understand the notion of a “bad boy” attraction: … but he’s neither charming nor handsome (rather, he’s oafish and crude). To that end, Jonathan Rosenbaum points out that “The melancholy trio of Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise (1984) … — two dandyish, deadbeat best friends and the shy, younger woman they’re smitten with — would have been inconceivable without Godard’s adorable threesome;” however, I’m not a fan of Jarmusch’s movie, and don’t consider the trio here (or there) to be anything close to “adorable”. One of this film’s most memorable scenes occurs when Karina, Frey, and Brasseur get up and begin dancing “The Madison” in a line: Indeed, Quentin Tarantino was smitten enough with this sequence to pay homage to it in Pulp Fiction (1994), when Uma Thurman and John Travolta boogie on the dance floor; but here it’s merely a diversion rather than — as Godard’s somber voiceover claims — an opportune moment to offer “a digression in which to describe our heroes’ feelings.” While most film fanatics will be curious to check out this historically influential film, I don’t consider it one of Godard’s must-see movies. Notable Performances, Qualities, and Moments: Must See? Links: |

One thought on “Band of Outsiders / Bande à Part (1964)”

First viewing. Not must-see.

Though I can’t swear to it at the moment, this may be Godard’s most straightforward film, seemingly designed to play out faithfully as a pulp B-movie. So there’s very little to distract from that goal – and, for a change, there are lots of actual, genuine-sounding conversations (not worthwhile ones, necessarily, but they’re strung together successively to achieve the flow of a more-standard film).

To me, this feels like Godard’s inverse response to Truffaut’s ‘Jules and Jim’. To suit Godard’s anarchic style, the danger comes not from the woman but from the men (which makes the famous dance sequence midway all the more endearing, since it’s so unexpected and a welcome intermission of joy).

Frey and Brasseur are serviceable as the odd couple thugs but Karina does suffer under the weight of her strangely conceived role.

When it comes to the actual robbery, it’s handled with surprising aplomb (with its unanticipated setbacks).

Additional plus factors are Coutard’s splendid and endlessly varied location camerawork as well as Michel Legrand’s inventive score.

Still… the overall effect of the film is one that’s cold, distant; uninterested in whether the viewer is engaged or not.

The ‘Village Voice’ called the film “a Godard film for people who don’t much care for Godard” – which I would say is accurate. At least it’s not overtly annoying. It’s the only Godard film listed in ‘Time’ magazine’s ‘All-Time 100 Movies’, so – even though I don’t think of this film as must-see – ffs can relax knowing they can experience a reasonable Godard film that probably won’t infuriate them.