|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Detectives and Private Eyes

- Edward Dmytryk Films

- Gloria Grahame Films

- Jews

- Murder Mystery

- Robert Mitchum Films

- Robert Ryan Films

- Robert Young Films

- Soldiers

Review:

Edward Dmytryk’s adaptation of Richard Brooks’ novel The Brick Foxhole is notable both as the first B-level film to be nominated for an Oscar as Best Picture of the Year, and for running neck to neck with Gentleman’s Agreement (1947) as one of the first Hollywood movies to openly address anti-semitism. Ironically, Brooks’ novel was actually about homophobia, a topic banned at the time by the Production Code. However, unlike Brooks’ own directorial adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ Cat On a Hot Tin Roof (1958) — which suffers from a fatal loss of sensical motives when Paul Newman’s homosexuality is taken out of the storyline — the thematic switch here works fine; it’s easy to be convinced that anti-Semitism (ever present, albeit often in more subtle forms) might drive a senseless murder like this one. As Dmytryk wrote in his autobiography:

After our rough-cut showing to the sound and music department, one of the young assistant sound cutters, an Argentine, complimented me on the picture.

“It’s such a fine suspense story,” he said. “Why did you have to bring in that stuff about anti-Semitism?”

“That was our chief reason for making the film,” I answered.

“But there is no anti-Semitism in the United States,” he protested. “If there were, why is all the money in America controlled by Jewish bankers?”

I stared at him in astonishment. “That’s why we made the film”, was all I could think of to say.

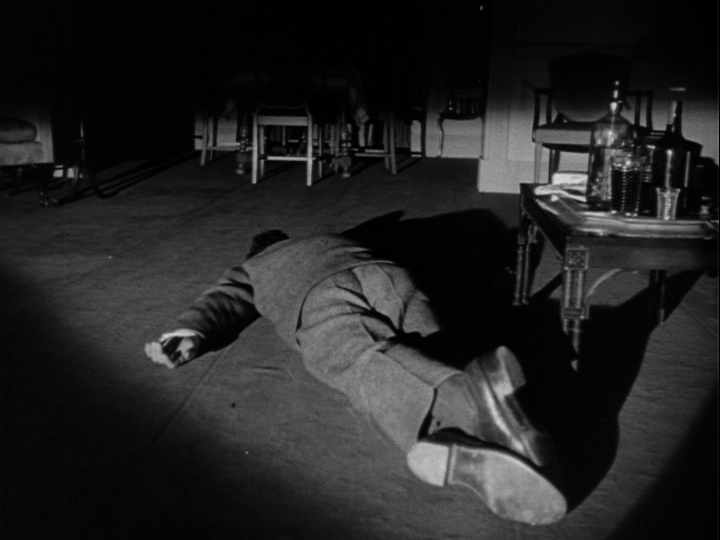

As a noir, Crossfire works exceptionally well, with each frame maximizing use of light and shadow to heighten the drama and suspense; Dmytryk and his crew managed to get the film made with only 150 set-ups (be sure to listen to the commentary soundtrack on the DVD to learn more about the film’s production, as well as Dmytryk’s blacklisting by HUAC). Equally impressive are the stellar performances, most notably by Ryan: check out his soulless eyes as he tells a faux flashback tale to Young, and his chilling scene with terrified Steve Brodie as “Floyd”.

Grahame is also a stand-out in her supporting role as a world-weary dance hall girl with a mysterious man (Paul Kelly) living in her apartment.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Strong performances across the board

- Dmytryk’s creative direction

- J. Roy Hunt’s cinematography

Must See?

Yes — definitely check this one out. Listed as a film with Historical Importance in the back of Peary’s book.

Categories

Links:

|

2 thoughts on “Crossfire (1947)”

I was on a Robert Ryan kick last year and got this from Netflix. Memory is fuzzy on a lot of the narrative, but I remember Ryan’s character as horribly manipulative and effectively menacing and there being more than adequate tension. I would love to watch this noir classic again soon.

No-brainer must-see, and it holds up well on (and possibly benefits from) repeat viewings.

To my view, this is a perfect film, even considering the ‘necessary’ central switch from homosexuality to anti-Semitism.

In the DVD’s short backstory extra, Dmytryk talks about the process of working around authority figures without *always* doing exactly what they want done. For example, although the angle on homosexuality is removed, it does not seem to be removed completely. Nothing is overt in the film as it is, but there is at least the suggestion of bisexuality or closeted homosexuality playing a part in some of the muddy elements of the plot. (It doesn’t need to be overt.)

As Dmytryk explains in the same extra, the audience for the film was mainly gathered through its being a rather detailed (and cleverly constructed) murder plot. All other elements in the film – including the additional subplots of a) the psychological effects of war on soldiers, and b) a soldier’s feeling of inferiority as he tries to re-establish himself in society – take a back seat to the murder story that easily takes up the largest chunk of the film.

It’s only near the end that the film begins to feel ‘comfortable’ enough letting go of being a genre film to make way for the social statement it wishes to make .

And what a statement it is. When he talks to the young soldier who eventually helps him crack the case, Young makes a very compelling remark about what really happens in the underbelly of life: “That’s history, Leroy. They don’t reach it in school, but it’s real American history just the same.” In school, we do seem to be taught more often about the general facts of what happens, but much less about the real, unvarnished reasons why.

In Kazan’s ‘Gentlemen’s Agreement’, the reality of being Jewish is hammered over the heads of its audience from start to finish. That’s not a criticism (I’m a great admirer of that film). But in ‘Crossfire’, the same point is made clear in a fraction of the time – pointing up the fact that, in one main sense, the various reasons for or behind prejudice can be irrelevant: bigotry is wrong; end of argument.

‘Crossfire’ shows Dmytryk in very fine form in his direction – and he gets sharp, fully committed performances across-the-board from his cast. (Grahame – doing some of her best work here – gets most or all of the best wisecracks, i.e. “What do you want from me – a character reference?”)

Note: Is this the only film in cinema history that boasts three leading actors having the same name of ‘Robert’? …Possibly.