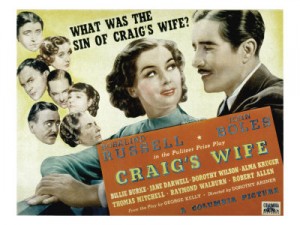

Craig’s Wife (1936)

“Nobody can know another human being enough to trust him.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Review: Watching Harriet Craig a few years ago was my personal introduction to Kelly’s play; viewing it once again (albeit in a truncated fashion; this film runs just 73 minutes, 21 minutes less than Harriet Craig), I had a renewed appreciation for the important themes he’s attempting to address, and I found myself doubly thankful that this earlier version was directed by Dorothy Arzner, whose feminist sensibilities shine through clearly. Indeed, Russell’s Harriet comes across as nothing less than a deeply self-preserving woman who recognizes that her only chance at security in life is wooing a well-off man who will give her whatever she wants; her mistake, of course, lies in failing to recognize that longevity requires more than just this initial conquest. To that end, I remain troubled in both adaptations by the unrealistic character arc of Craig’s husband, who shifts from adoring puppy (how can he be so clueless?) to wounded cynic far too quickly — but this time around, I found myself better able to understand the need for dramatic compression (this is an adaptation of a play, after all). Ultimately, both Craig’s Wife and Harriet Craig remains worth a look by those interested in engaging with the play’s challenging yet provocative premise. Redeeming Qualities and Moments: Must See? Links: |

2 thoughts on “Craig’s Wife (1936)”

A must – as (most likely) Arzner’s best film, and for the cast’s solid performances, esp. Russell in her breakthrough role. The film holds up well to multiple viewings.

I had to do something I had been neglecting to do for a long time: I finally read George Kelly’s play. I’ve seen the Russell and Crawford film versions a number of times each – and remained intrigued as to how the two could be somewhat disparate yet essentially the same. The original play did shed some light.

Arzner’s film is a 75-minute pressure cooker derived from a three-act play. The play is over-written: there are scenes in it that are unnecessary due to repetition; other scenes are unnecessary because they are too peripheral to the main action. One must assume the purpose of the length was to make for a more leisurely dramatic evening in the theater. (But I still think Kelly needed the firm hand of a dramaturg.)

Arzner’s screenwriter, Mary C. McCall, Jr., concocted a marvel in screen adaptation. She took out what wasn’t needed from the play while capitalizing on certain elements that were rife with cinematic possibilities. Whereas the play occasionally gets bogged down, the screenplay moves like a bat out of hell.

When it comes to the Crawford remake – ‘Harriet Craig’ – Kelly’s play is certainly there in the spine and the basic structure. At the same time, however, there is considerable embellishment – and a number of off-shoots. In both films, Harriet is seen as a force to be reckoned with – but Crawford’s Harriet appears more ambitious in her goals (certainly more clingy when it comes to her husband); Roz, on the other hand, plays a Harriet who obviously cares much less about her husband and is more quietly afraid of the world and everyone in it. (As well, the Crawford version, in keeping with the trend in 1950, tends to be a lot more pointedly psychological.)

It’s interesting to note the rare instance in film history in which two very strong films – with two very strong leading female performances – can be compared and contrasted. Each has its own strengths. Neither one has particular weaknesses.

As much as I like ‘Harriet Craig’, however – for me, it runs a close second to Arzner’s work. I probably prefer the fact that the Russell film is simpler in narrative. (Though I stated in my ‘Harriet Craig’ post that a thesis could be written on it; the same goes for ‘Craig’s Wife’.) And I like a number of the scenes based on what was only talked about but not shown in the play (i.e. the subplot of troubled Thomas Mitchell’s own doomed marriage – by the way, note what Mitchell’s wife says to him re: Boles as she’s about to go out for the evening: “Run on back to your boyfriend, dear.” Boyfriend?!)

[Note: a significant cut from the play comes when Mr. Craig advises his niece and her fiance: “The only thing I think you need to consider really seriously — is whether or not you are absolutely honest with each other.” A solid bit of advice which would have been nice to hear in the film.]

One thing about Boles’ Craig. Craig and his wife have been married for two years. If you watch Russell very carefully, you can see how she has been able for two years to maintain a charming and sexual front with her husband. She’s been acting – and he has responded as if she meant it. But, as Russell plays her, Harriet is now beyond the honeymoon and on to more ‘practical’ matters. Her husband is still enjoying the ‘honeymoon’. As Craig’s aunt tells him, “You’re a man, Walter, and you’re in love with your wife.” He’s been blinded by the impeccable performance Harriet has displayed for him. He also finds her hot.

But things are about to change in this 24 hours – when Harriet comes undone as her ‘world’ falls apart around her. Harriet could count on people being quiet in front of her husband; she has him mesmerized. But Harriet didn’t figure on being implicated in a murder – who would? And even though she and her husband are only on the skirt of the issue, that unforeseen incident will challenge everything Harriet has carefully constructed. Her ‘performance’ will be harder to repeat. The mask will sometimes drop. She will make mistakes. She may finally be forced to face herself.

Much prefer the Rosalind Russell version. She was so good and she must have jumped at the chance to play such a great role.

I liked Alma Kruger as Walter’s aunt who remarks to him that she overheard a man saying to his wife – “Who do you think you are, Craig’s wife?”

And, at the end, before he leaves, Walter says to Harriet – “You married a house and I’ll see that you have it always.”

There was an earlier film version, starring Irene Rich and Warner Baxter.