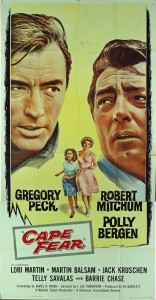

Cape Fear (1962)

“A type like that is an animal — so you’ve got to fight him like an animal.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Response to Peary’s Review: We’re shown exactly what kind of a self-centered bastard Mitchum is during the opening sequence, as he jostles a woman carrying a stack of books, and walks right past her rather than stopping to help her pick them up. Later, an encounter between Mitchum and a “loose” woman (Barrie Chase) he picks up at a bar — then attacks so viciously she’s scared to say a word to the authorities — is used to excellent effect, indicating to us exactly the level of violence and sexual terror Mitchum is capable of inflicting; while the “attack” itself isn’t shown explicitly, the way in which director J. Lee Thompson shows both the terrifying moments beforehand, and Chase’s brutalized appearance after, are enough to convince us that Mitchum is someone of whom to be very, very scared. Meanwhile, Bernard Herrmann provides an effectively creepy film score, and accomplished DP Sam Leavitt’s b&w cinematography is consistently atmospheric. With all of this said, I personally find Cape Fear too disturbing a film to recommend as more than a “once-must” thriller. While the entire story is told remarkably effectively, who wants to subject themselves to this kind of vicarious torture more than once? I know there are horror fans who live for the opportunity to exist with their hearts perpetually in their throats; but the type of menace offered up here is simply too freaky for my blood. The basic premise of the screenplay is that the law won’t — or can’t — protect citizens from an uncommitted crime, no matter how obvious the threat. To that end, as noted by Richard Scheib, Cape Fear is notable as “the first of a subgenre of films that placed the nuclear family and the values of ordinary American decency up against a wall”, with “direct echoes… found in films like Straw Dogs (1971) [and] Dirty Harry (1971).” While it may be astonishing to see Peck — starring as a pacifist lawyer in the same year’s To Kill a Mockingbird — resort to violence to protect his own family, one seriously can’t blame him. Redeeming Qualities and Moments: Must See? Categories

Links: |

One thought on “Cape Fear (1962)”

Agreed, a once-must. Probably for the reason stated. It’s certainly well-crafted enough for a repeat, but you may find yourself putting years between an initial visit and a return. I certainly did.

I don’t actually find it quite as disturbing as is noted here. Part of the reason for that is that the content (overall) sounds a lot more menacing to us than what we see. I mean that more literally: ‘CF’ is more disturbing to listen to than to watch; we see very little actual violence. We do, however, have to listen to two very menacing elements: just about everything Mitchum says is very unsettling for one reason or another (i.e., about Peck’s very young daughter, Mitchum says, to Peck’s face: “She’s getting to be as juicy as your wife.”); and, of course, there’s Herrmann’s unnerving score (just as powerful as his ‘Psycho’ score, with more an air of fiercely determined stalker, as opposed to crazed attacker).

It’s odd that many people feel Scorsese’s 1991 remake (with cameos by Peck, Mitchum and Balsam – and which has the threatened family appear more flawed) is the superior film. It’s not. At all. It does have one main thing in its favor: the reason Cady seeks revenge runs slightly deeper (and, apparently, closer to the novel). Other than that, I’ll pretty much take the original.

The original though, does make one wrong move for the sake of drama: as soon as Peck realizes his family is in serious danger, he gives his daughter (and wife, one would think, since she’s there at the time and hears him) explicit instructions about being careful. In one very intense scene, the daughter is left alone in the family car while the wife goes to the store “for a second”. Why couldn’t the daughter be with her? There’s no reason – except that Mitchum is given a chance to stalk. And when he approaches, why does the daughter run away into a building, when she’s much safer outside among people? There’s no reason – except that Mitchum is again given a chance to stalk.

For me, one of the most interesting aspects of the original is the daughter. When we first meet her, we’re led to believe she’s a passive little thing – and, therefore, an easy target. We learn, though, refreshingly, that she takes after her father and, in some ways, is made of tough stuff.

‘Cape Fear’ does indeed make a very powerful statement about lack of protection, when it couldn’t be hiding more in plain sight that it’s needed. It’s true – when the law won’t or can’t be there for you, you will have no choice but to be much more clever than the one threatening you.