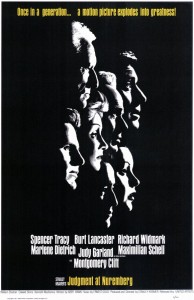

Judgment at Nuremberg (1961)

“We must forget if we want to go on living.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Review: Judgment at Nuremberg, despite its strengths, is a uniquely challenging courtroom drama to sit through, given that we’re not meant to judge whether the sentences received by the two victims who testify in court — a mentally challenged laborer (Montgomery Clift) sterilized for his Communist associations, and a young Aryan woman (Judy Garland) imprisoned for her friendship with an older Jewish gentleman — were just or not; of course they weren’t. What’s actually at stake here is whether the judges on trial were right to sentence these individuals as they did. Interestingly, the broader context of the trials — i.e., the question of whether Americans and others even had a “right” to come in to Germany and prosecute its citizens in such a manner — is only explored through the perspective of the Germans (such as Marlene Dietrich’s widow, Maximillian Schell’s defense attorney, and Burt Lancaster’s judge) who bitterly resist this imposition. Otherwise, the only non-German perspective we get on the matter is when a judge is cautioned to acquit the defendants as a strategic Cold War maneuver, to maintain good relations with the country. Viewers will be left to decide for themselves whether the trials themselves were ultimately warranted or not. The Oscar-nominated performances throughout, naturally, are top-notch, beginning with Tracy’s subtle yet powerful turn in the tricky central role; we empathize with his situation every minute he’s on-screen. Clift is simply phenomenal in a scene-stealing turn as a mentally challenged young man who struggles to articulate his thoughts, yet knows that what was done to him was not right. Garland’s supporting role is less showy, but she’s also impressive — and, as many have noted, her performance here was clear evidence of the type of “serious” role she could have excelled at if her life had taken a different set of personal turns. Richard Widmark is appropriately cast as a righteous prosecutor convinced that the judges must pay for their actions, while Oscar-winner Maximillian Schell (who Peary argues didn’t actually deserve the Best Actor award, given that his role is more of a supporting one) convincingly portrays the pride and indignation felt by occupied Germans after the war. Note: Kramer’s attention to detail throughout the film is rigorous and noteworthy — including the clever way in which he has the actors switch from engaging in simultaneous German/English translation to simply speaking in English, with the implicit acknowledgement that we’re meant to “hear” them as still speaking in their native language. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

Links: |

One thought on “Judgment at Nuremberg (1961)”

A very powerful must-see.

This could be director Kramer’s best film. One would think that the main reason Kramer didn’t actually direct more films (he made 20) was because a good part of his career was spent producing films as well (he produced 40). It seems he mostly put on his director’s hat when he had something on his mind that he thought the world needed to see. And the world did – and still does – need to see ‘Judgment at Nuremberg’. It’s a film that should be required viewing, whether you have much interest in films or not.

Like Preminger, in a way, Kramer tended to zero in on ‘hot topics’ – when we think of films such as ‘Inherit the Wind’, ‘On The Beach’, ‘The Defiant Ones’ & ‘Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?’ (Thank goodness he thought to lighten up at one point with ‘It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World’!) Without knowing much about ‘JAN’, it would be easy to think of it as merely one of many, many Holocaust films. And, in a way, that’s true. But its concerns are larger: somewhat indirectly (though this is touched on in Schell’s remarkable speech late in the film), it addresses how those at the highest levels of government and the military – almost anywhere – have always operated. (Which is most likely why this film will always be relevant; there will always be those whose hunger for power will make everything and everyone else subservient to it.)

In the film, a judgment is, of course, ultimately made. But it’s less a judgment on those who orchestrated evil (Hitler and his ‘pals’) than those who were afraid of it (who perhaps thought it was a matter of ‘kill or be killed’) or those who couldn’t find courage to act once they realized they’d been duped. (There is some mention of the fact that Hitler had morphed from what he first pretended to be.)

The film raises more questions than it can possibly answer. Like ‘Rashomon’ in a way, Abby Mann’s remarkable screenplay (which very much deserved its Academy Award) presents the various ‘truths’ behind what happened when things went mad in Germany. In his presentation, Mann is fair to all of the characters. Most of the people we see in this film remain trapped in a nightmare that swallowed them up. The overriding concern of ‘JAN’ is the question of responsibility: what is an individual’s choice (if there even is one) when facing something on the level of Hitler’s heart of darkness?

It’s not easy to come to terms with a film like this, especially when the blame ends up shooting out in more directions than one can keep up with – several of which, again, are referred to in Schell’s aforementioned speech.

As for the performances, this is a rare instance in which actors known for giving standout performances in other classic films simply pull together for the sake of story. There is not one particular performance that stands out from the rest – it is fine ensemble work.

Note: If you do a search at YouTube, you can find what amounts (in 6 clips) to a 3-hour interview with Abby Mann, conducted a few years before he died in 2008. Mann had a long career writing for the theater as well as tv and film. He talks quite a bit about the writing and filming of ‘JAN’. Fascinating viewing.