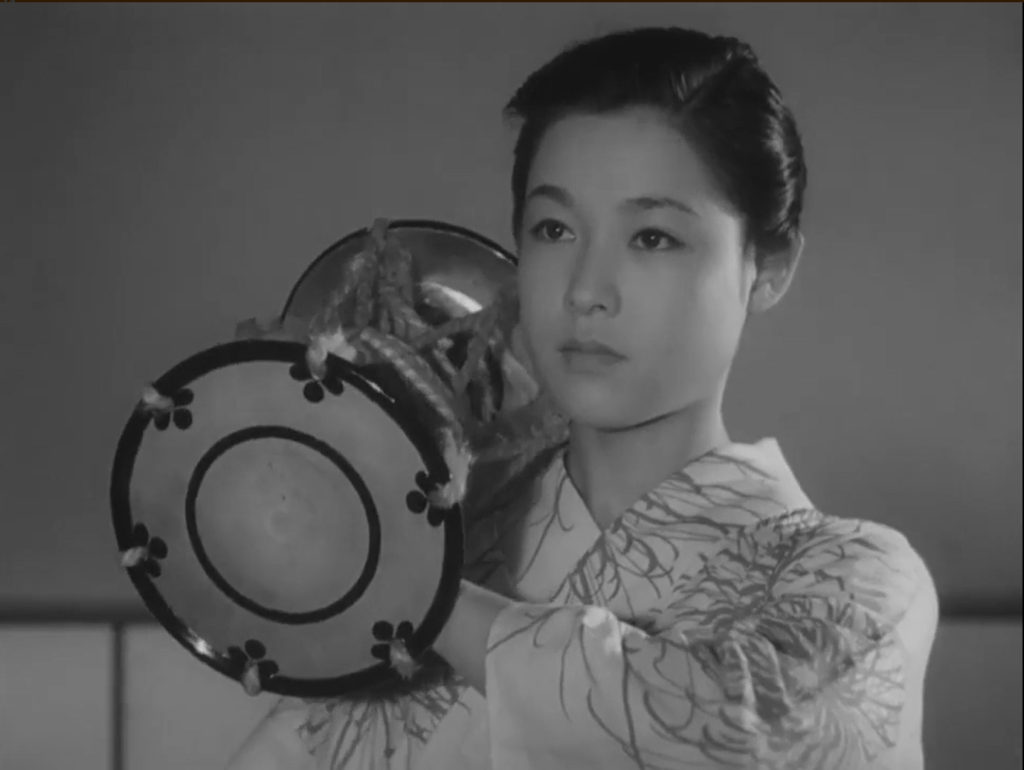

Geisha, A / Gion Bayashi (1953)

“Geisha don’t lie — they talk business.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Review: Fortunately, Mizoguchi makes no such mistake in his film. Time and again in Gion Bayashi, men (without a single exception) are shown exploiting geisha for any of numerous reasons: their personal sexual gratification (Kawazu nearly rapes the adolescent Eiko, while Koshiba calls Miyoharu “cold” for refusing his advances); to advance their business (“renting” the right geisha for one’s clients can help grease transactions); or for cold, hard cash (Eiko’s deadbeat dad refuses to help sponsor her training as a geisha, but comes begging for handouts once she’s successful). In addition, unlike in Memoirs, the geisha “sisters” in this film don’t develop cut-throat rivalries with one another; instead, they understand that camaraderie and empathy is what will help them survive. In perhaps the most interesting scene of the film, Miyoharu sits with Eiko after she has severely compromised their reputations by fighting back during an attempted rape by Kawazu (she bit his mouth so badly he was hospitalized for a month). Rather than chastising Eiko, however, Miyoharu admits that she would have done the same thing. Eventually, Miyoharu becomes a mother-figure of sorts to Eiko, attempting to protect her at all costs from the debasement geisha face in a modern world which no longer respects their work — and it is hard, difficult work — as a noble craft. Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

Must See? Categories

Links: |

One thought on “Geisha, A / Gion Bayashi (1953)”

A satisfying must on all counts, and one of Mizoguchi’s finest films.

Kogure and Wakao are nothing short of perfection – not only as, respectively, representations of pre- and post-war attitudes, but as two women who share one of the ‘worst’ attributes possible for their situation: an independent spirit. They learn all too quickly that an almost-literal brick wall will block them (as well as shut them out) if they refuse to (literally) bow to a world of buy-and-sell.

Money, loyalty and submission are everything in this world. In a very economical 83 min. (which seem to fly by), ‘A Geisha’ takes a semi-documentary approach – in the sense that the specifics of this life are brought out in montage visuals or in dialogue, so that the audience knows exactly what a geisha is made of and what is expected of her.

Given a woman’s options at the time, it was then a world of ‘privilege’. Of course, you had to relinquish your soul… The almost-complete downfall of the protagonists is in realizing that they *have* souls.

Mizoguchi’s nuanced direction is on-target; clearly, his sympathy rests with his sisterly leads, and them alone.

Special mention: ‘A Geisha’ was filmed exquisitely in b&w by Kazuo Miyagawa, who collaborated not only on some of Mizoguchi’s best films – ‘Ugetsu’, ‘Sansho the Bailiff’, ‘Street of Shame’ – but also a fair amount of the director’s less-known work; he also had occasion (for examples) to work with Kurosawa (‘Yojimbo’), Ichikawa (‘Enjo’) and Ozu (‘Floating Weeds’). An ace cinematographer.