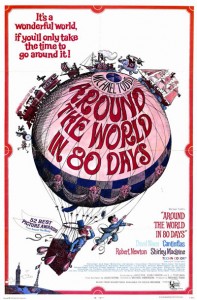

Around the World in Eighty Days (1956)

“An Englishman never jokes about a wager.”

|

Synopsis: |

|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

Review: As an adventure story, however, Around the World… falls surprisingly flat. Despite the built-in drama of Fogg literally racing against time to make it back to London (with his entire fortune at stake), the film takes its own sweet time stopping at sundry picturesque destinations, as various minor subplots are played out. A major narrative thread — involving a detective (Robert Newton, in his last film role) attempting to nab Fogg as a suspect in a bank robbery — is merely irritating, given that Newton literally shadows Fogg the entire trip, and should just arrest him already if he’s going to (though that would spoil the film’s infamous twist ending). Meanwhile, Fogg’s growing romantic interest in a widowed Indian princess (Shirley MacLaine) rescued from a funeral pyre generates zero sparks, and is frustrating to watch given that it’s Passepartout, not Fogg, who risks his life to rescue her (but does she acknowledge him at all? not a chance!). Speaking of Cantinflas — while there’s a certain historical interest in seeing the man who was the highest paid actor of his time (and I’m happy, as a Western viewer, to at least be acquainted with him), both his performance and his character are, to be blunt, irritating. (I’m sure he must have been more entertaining when filming in his native language in straight comedies — right?). Meanwhile, MacLaine — in skin-darkening make-up and Indian outfits — simply looks uncomfortable throughout, and barely registers (which is truly odd, given her notoriously quirky personality). And while Niven purportedly named this his favorite role of all time, his Fogg ultimately comes off as a rather bland (if undeniably resourceful and resilient) chap. Niven, MacLaine, Newton, and Cantinflas are, of course, only a handful of the many “big name” stars who appear in the film — indeed, so many show up for cameos that this is credited as the movie that first popularized the term (and general concept) of a “cameo appearance”. And there is undeniably a certain amount of fun to be had in scanning for stars’ faces, given that they show up again and again; you may find yourself muttering out loud, “Could that be… Really? Yes, it is! But (s)he doesn’t even say a word!” As Peary notes in his Alternate Oscars book, it was rather wise of Todd to offer “cameos to almost every actor in the universe”, since, as he notes, “How could the Academy members vote against their friends?” Touche. Note: Saul Bass’s immensely clever closing credits (which essentially summarize the film in creative caricatures) are a fabulous ending to this dauntingly long (183-minute running time) film. On that note, you can cut at least a little bit out if you watch it at home on DVD, given that there are Entr’acte and Exit musical sequences to fast-forward through (the musical score is catchy, but not THAT catchy!). Redeeming Qualities and Moments: Must See? Categories

Links: |

One thought on “Around the World in Eighty Days (1956)”

Skip it – save yourself three hours of extremely lackluster ‘entertainment’.

I hadn’t seen this since I was a wee tyke; I have only the vaguest of memories of watching it on television. I actually dreaded a revisit, for the purpose of this posting. As it turns out, my fear was real.

This is truly one of the dullest films ever made. It’s not that it’s bad in an incompetent way – it’s that it’s done in by its own earnestness.

I don’t know any film fanatic who ever mentions this film. For a film that actually won the Best Pic Oscar, that’s sad in itself. Films of this sort – though not exactly designed as ‘Oscar bait’ (a term now in fashion, usually when talking about individual performances) – have the goal of being blockbusters. They are meant to make money due to their ‘bigness’. But there’s ‘bigness’ and there’s ‘bigness’. ‘Bigness’ for its own sake = bloated.

Look at the other films nominated for Best Picture Oscar that year: ‘Friendly Persuasion’, ‘Giant’, ‘The King and I’ and ‘The Ten Commandments’. (Not exactly a year of tough competition.) All 5 films are probably guilty of being overly earnest – and, with the possible exception of ‘Friendly Persuasion’, they all wear blockbuster labels. Ultimately, none of them are particularly great films (even the blockbusters) – since a certain blandness runs through all of them. It’s not easy being a blockbuster *and* a great film.

Myself, I’d have given the Oscar to ‘The Ten Commandments’. At least it’s wonderfully entertaining (if often for the wrong reasons).

It’s kind of amazing that Niven remains consistently stoic throughout; for that he does earn points. I did get a tiny kick out of (early on) Noel Coward and John Gielgud in their scene together. And Ronald Colman appears to slightly breezy effect.

But the only performance that gave me any genuine pleasure is given by good old Buster Keaton as a railroad worker. His appearance is the single thing here that made my smile.