|

Genres, Themes, Actors, and Directors:

- Character Arc

- City vs. Country

- Femmes Fatales

- F.W. Murnau Films

- Homicidal Spouses

- Janet Gaynor Films

- Silent Films

Response to Peary’s Review:

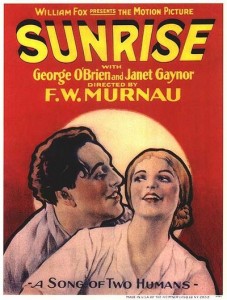

Peary writes that F.W. Murnau’s “American debut” remains a “great silent film”, one which “takes a simple, universal story and gives it startling emotional impact through breathtaking camera work”. He argues that “between The Birth of a Nation and Citizen Kane there is no better example in American film of visual storytelling”, given that the “expressionistic (sometimes lyrical) film… reveals the psychology of its characters from movement to movement through intricate lighting, camera movement and positioning, choice of setting, scenic design, and superimpositions (that reveal thoughts) and other special effects”. He points out that the “picture has a European look because it was designed in Germany before Murnau came to the U.S.”, and argues that the “acting is fine, with Gaynor and O’Brien showing why they were one of the era’s most likable screen teams, and Livingston making a devilish femme fatale“.

In his Alternate Oscars book, Peary names Sunrise the Best Picture of the Year, arguing that the actual winner, William Wellman’s Wings (1927), “pales in comparison” and “has dated badly”, and pointing out that Sunrise actually won the “Artistic Quality of Production” award, a category which was soon abandoned and is no longer remembered.

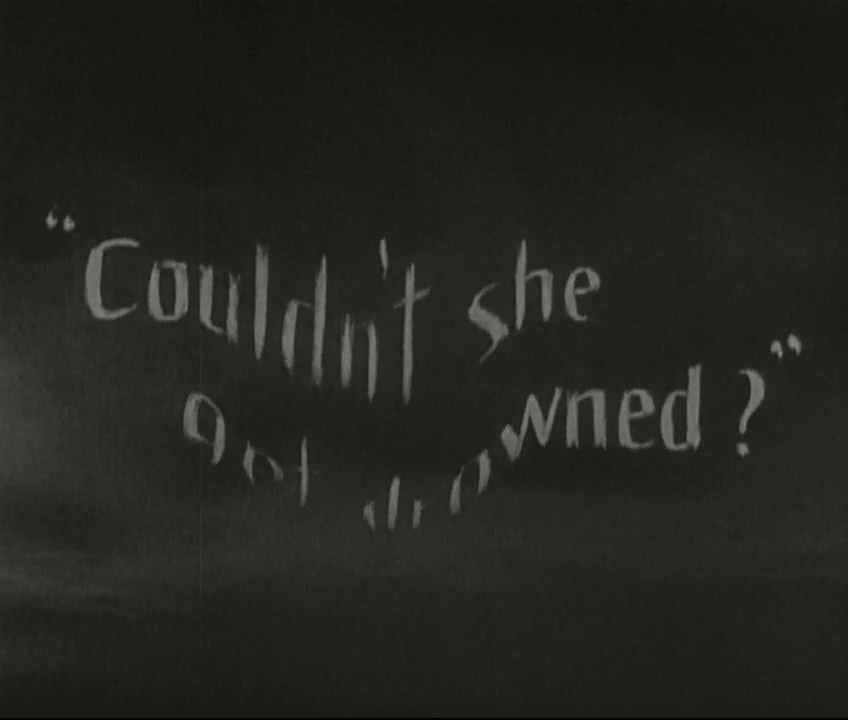

Peary’s not at all alone in his laudatory view of this visually stunning silent film, which is consistently innovative and atmospheric in its presentation style. However, one’s enjoyment of the story itself will depend greatly on an ability to view it as a fable rather than a realistic tale of infidelity and renewed marital trust. After all, Gaynor’s The Wife (as in Murnau’s equally fable-like The Last Laugh [1924], the major characters aren’t given names) manages to fairly quickly forgive her husband (The Man) for having homicidal tendencies towards her (!), allowing their New York trip to function as a second honeymoon rather than worrying about his dangerously mercurial nature. Meanwhile, the details of the entire narrative remain remarkably simplistic, in a fairy tale-like fashion; Peary himself refers to it as a “fable-morality play”.

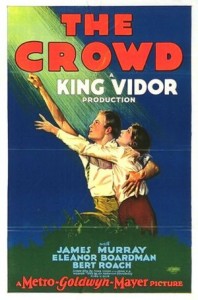

In Alternate Oscars, Peary notes that Vidor’s thematically similar masterpiece from the same year (The Crowd) is every bit as impressive and “artistic” as Murnau’s film, but that Sunrise was still a better choice as Best Picture of the Year (calculated at that point from August 1927 to August 1928), simply given that it “turned out to be more influential”. He points out that both films “are about how a married couple’s enduring love neutralizes the hostile, destructive, corruptive powers of the city”; indeed, having recently rewatched The Crowd myself, the similarities are strikingly notable. Yet I found myself much more emotionally engaged in the travails of The Crowd‘s realistic (albeit “every man”) protagonists, while Sunrise‘s The Man and The Wife simply function as convenient archetypes, held at remove. Indeed, at times Murnau’s film edges dangerously close to stereotyping in its overly-simplistic presentation of city-versus-country, with O’Brien and Gaynor shown as naive hicks who can’t quite keep up with the pace of city living.

With all that said, there really is no denying the visual impact of Sunrise, which uses cinematographic techniques to tremendous effect, clearly demonstrating once again why F.W. Murnau is considered a pivotal figure in the early days of feature-length cinema. For that reason alone, it’s most certainly worth a look by all film fanatics.

Redeeming Qualities and Moments:

- Charles Rosher and Karl Struss’s cinematography

- Excellent use of “in-camera” effects

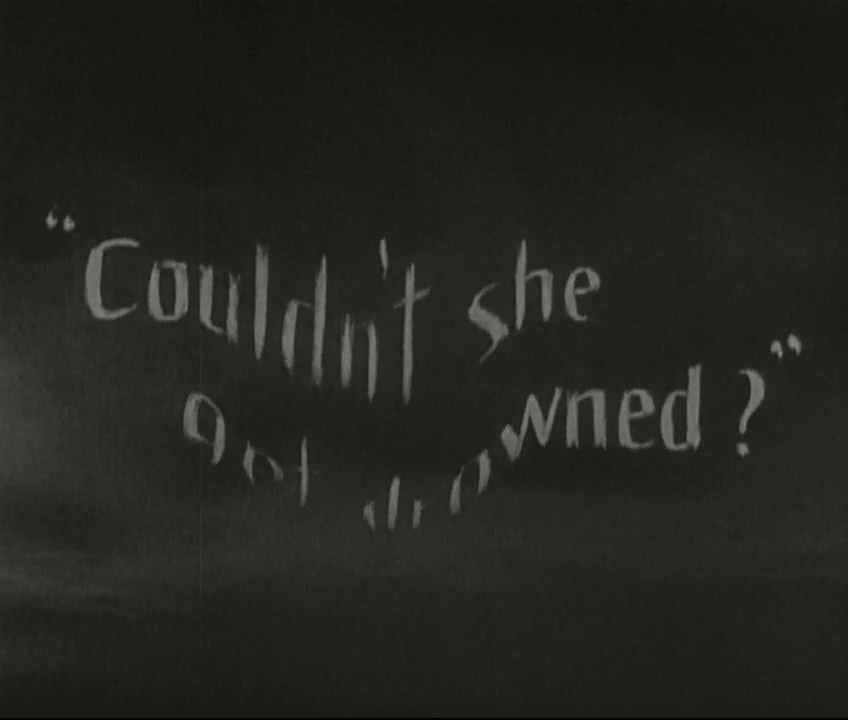

- Creative intertitles

- Atmospheric sets and art direction

Must See?

Yes, as a visually evocative silent classic.

Categories

- Genuine Classic

- Important Director

- Oscar Winner or Nominee

(Listed in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die)

Links:

|